What are the fundamental human needs, and why does it matter?

Can diving into the world's words make systems like the social determinants of health actually useful?

Note, though based on personal notes, much of this content was written and formatted by AI.

Abstract

I'm exploring how to identify the fundamental human needs in order to improve societal systems beyond our current models. Models like the Social Determinants of Health can diagnose social issues but lack insight in how to implement remedies. I assert that this is partly due to their lack of grounding in an empirical, cross-cultural and taxonomically complete model of fundamental human needs and desires. Inspired by personality trait mapping methods like the lexical hypothesis used for The Big Five and HEXACO, I'm exploring using AI to analyze language across cultures to identify universal human needs. By understanding these shared drives and applying frameworks like Ken Wilber's quadrants, I aim to develop the foundation for more culturally universal models of human thriving.

If our goal is to collectively build social structures that make human flourishing most likely in a highly interconnected, multicultural world with ever deepening meta-crises, an omni-lingual, cultural map of human needs and desires seems like a critical tool.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Introduction

The Need for a Universal Model of Human Needs

Beyond Existing Frameworks: A New Approach

The Complexity of Identifying Human Needs

Psychological Theories of Human Needs

Cultural Biases, not just “Western” ones

Individual vs. Collective Needs

Challenges with Currently Applied Frameworks: The Social Determinants of Health, a Case Study

Understanding the SDOH Framework

The Gap Between Individual and Systemic Needs

Critiques of the SDOH

Lessons from the Lexical Hypothesis and Personality Models

The Big Five Personality Traits

Limitations and Cultural Biases

The Discovery of Honesty-Humility and the HEXACO Model

Methodological Significance

Applying This to Understanding Human Needs

The Interplay of Individual and Collective Needs

Metaphysical and Ontological Considerations

Human Societies as Manifestations of Individual Needs

The Limits of Language in Capturing Human Needs

"The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao"

E.O. Wilson and Aristotle's Influence

Embedding Ultimate Causes in Language

Wittgenstein Revisited

Statistical Centers in High-Dimensional Semantic Vector Space

Proposed Methodology

Data Collection

Addressing Biases

Quadrant Segmentation

Semantic Embedding and High-Dimensional Mapping

Cluster Analysis and Identification of Statistical Centers

Validation and Iteration

Enhancing Methodological Robustness

Final Thoughts

Toward a More Inclusive Understanding of Human Needs

Building Societal Systems for Human Flourishing

The Role of AI and Linguistic Analysis in Understanding Needs

Recognizing the Limits of Cultural Perspectives

Designing Effective and Equitable Societal Systems

Introduction

The quest to understand fundamental human needs is essential for building societal systems that truly support human thriving. I am working on a project that maps complex systems of human interactions, and from this emerges the necessity to categorize, in a taxonomically complete way, all human needs. If we aim to track the activities of public and private institutions to assess how effectively they are working together and achieving their collective goals, we must understand what needs they are fulfilling.

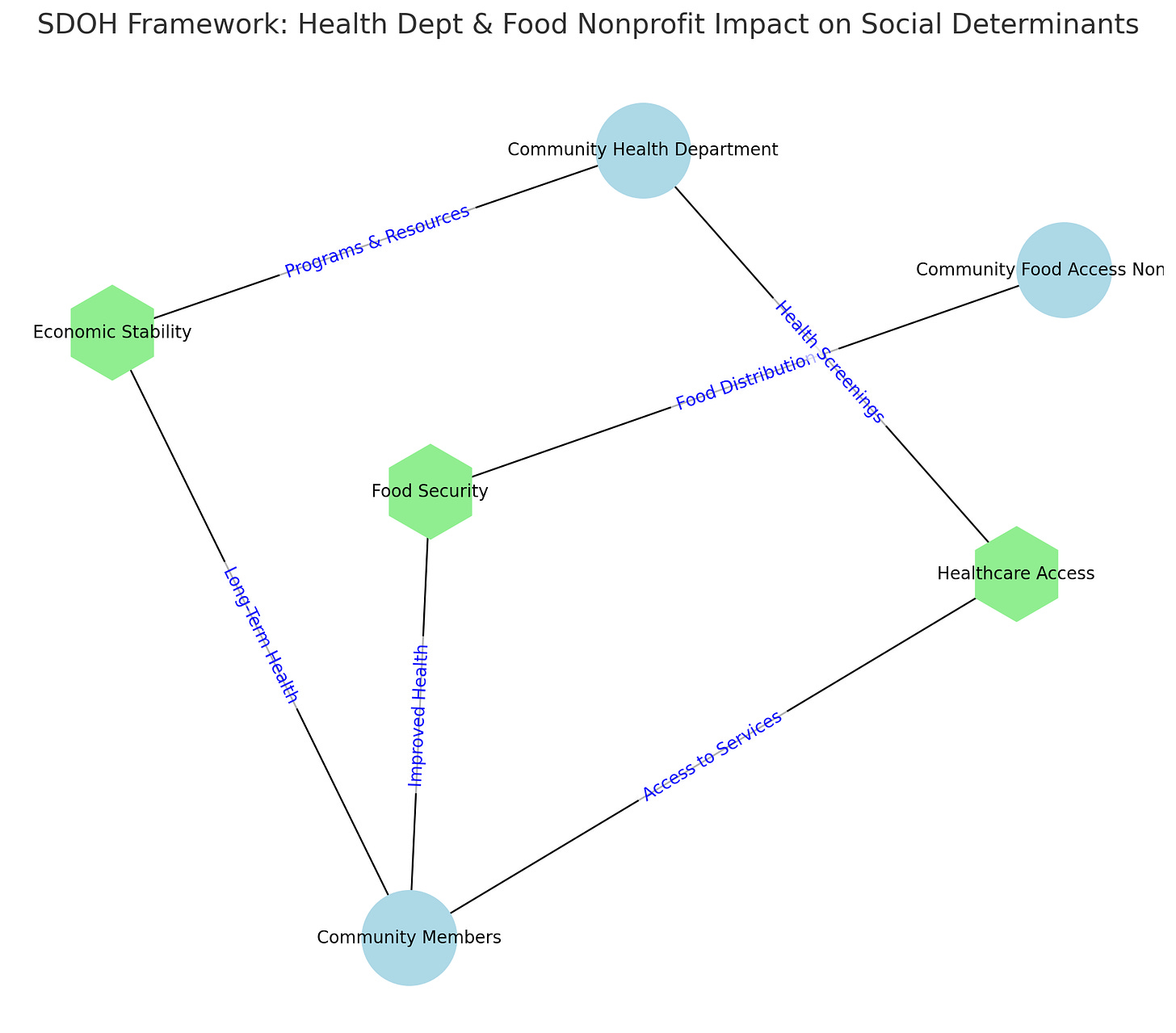

At first glance, this might seem like reinventing the wheel. Existing frameworks can help map interactions between entities like health departments and community food access nonprofits. For instance, we can generate a systems map outlining the interactions between these groups and community members, mediated by the human needs they are fulfilling: economic stability, food security, and healthcare access. This example is robust because many of these factors are framed by the term "Social Determinants of Health" (SDOH), representing elements that research has shown to impact overall health.

However, while these frameworks are helpful, they often lack a deeper understanding of the fundamental human needs that drive behavior across different cultures and contexts. We need a more robust, universally applicable model that transcends cultural biases and captures the essence of what humans need to thrive. Crucially, we aim to approach this without presuming that one cultural perspective—be it individualistic or collectivist—is inherently more correct than another. Our goal is to objectively explore underlying human needs that manifest across various cultural contexts.

The Complexity of Identifying Human Needs

Understanding human needs is inherently complex due to the subjective cultural lenses through which we view the world. Our cultural perspectives shape not only how we express our own needs but also how we interpret the actions and needs of others. This subjectivity creates significant barriers to recognizing that behaviors—even those we deem harmful—often stem from genuine human needs being met in maladaptive ways.

Psychological Theories of Human Needs

Various psychological theories have attempted to outline human needs, providing valuable insights into human motivation and behavior. Among the most influential is Abraham Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, which proposes a five-tier model of human needs, often depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid. The needs range from basic physiological requirements like food and shelter to higher-level psychological needs like esteem and self-actualization.

Another notable theory is Self-Determination Theory by Deci and Ryan, which emphasizes three innate psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These needs are considered essential for psychological growth, integrity, and well-being.

While these theories have contributed significantly to our understanding of human motivation, they often stem from Western cultural perspectives, carrying inherent biases. They tend to emphasize individualism over collectivism, focusing on personal achievement and autonomy. And what’s perhaps more fundamental, they view the individual as the ultimate subject of psychology, with little consideration for if the collective could in some sense be an observable entity with similar or unrelated needs to the individual.

This might seem pedantic, but even an apparently collectivist need like “belonging” is still, semantically, individual focused. It is framed that the individual has a need to feel in the collective. While this may seem rather non-sensical to rational Western ears, is it not possible to equally state that the collective needs the individual?

Consider the term Ubuntu, often translated as “I am because we are,” or even “humanity” in Bantu. It is often embedded in a larger phrase that further connotes its semantic meaning: "Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu," which translates roughly to “A person is a person through other people.”

To extrapolate a bit, we might say something like this: the individual self is the aperture through which we can experience the world, but the self only exists as it emerges from the collective.

Akin to the Advaita Vedanta axiom “Atman is Brahman” (the god inside of us is the same as the god outside of us), this seems to assert that the distinction in the self and other, the individual and the collective, the microcosm and the macrocosm, is a distinction in perspective, emerging only through speech and its ability to linguistically differentiate self and other. As Wittgenstein is keen to remind us, it is our words that limit what we can see in the world.

This is not to say that Western psychologists are wrong and Zulu shaman are right — but to show that there are fundamental differences in the ontological perceptions of reality when it comes to self and other at work when we look at human needs. If we are trying to build systems that are designed to maximize the potential for human flourishing, we need to get into these spaces where we ask genuinely: “what is humanity?”

Cultural Biases, not just “Western” ones

The individualistic orientation of these psychological theories may not account for how needs are experienced and prioritized differently across cultures. For example, in collectivist societies, the sense of self is deeply embedded within the community, and fulfilling collective needs may take precedence over individual desires.

This ontological difference in the conception of the self influences how needs are perceived and met. Our reliance on Western psychological theories may limit our understanding of what people genuinely need to thrive. We must acknowledge that both individualistic and collectivist frameworks offer valuable insights but also have limitations in capturing the full spectrum of human needs.

Individual vs. Collective Needs

The tension between individual and collective needs is a central challenge in developing a comprehensive understanding of human needs. Individual pursuits might conflict with collective well-being, creating tensions not adequately addressed in traditional psychological models. For instance, an individual's desire for personal freedom might clash with societal norms designed to maintain collective order.

However, we are not suggesting that prioritizing individual needs is inherently flawed or that emphasizing collective needs is the solution. Instead, we recognize that without an objective understanding of underlying human needs and desires, we cannot determine which approach is more appropriate. Our goal is to explore these complexities without bias, aiming to understand what we genuinely desire and need as human beings.

Challenges with Currently Applied Frameworks: The Social Determinants of Health, a case study

Understanding the SDOH Framework

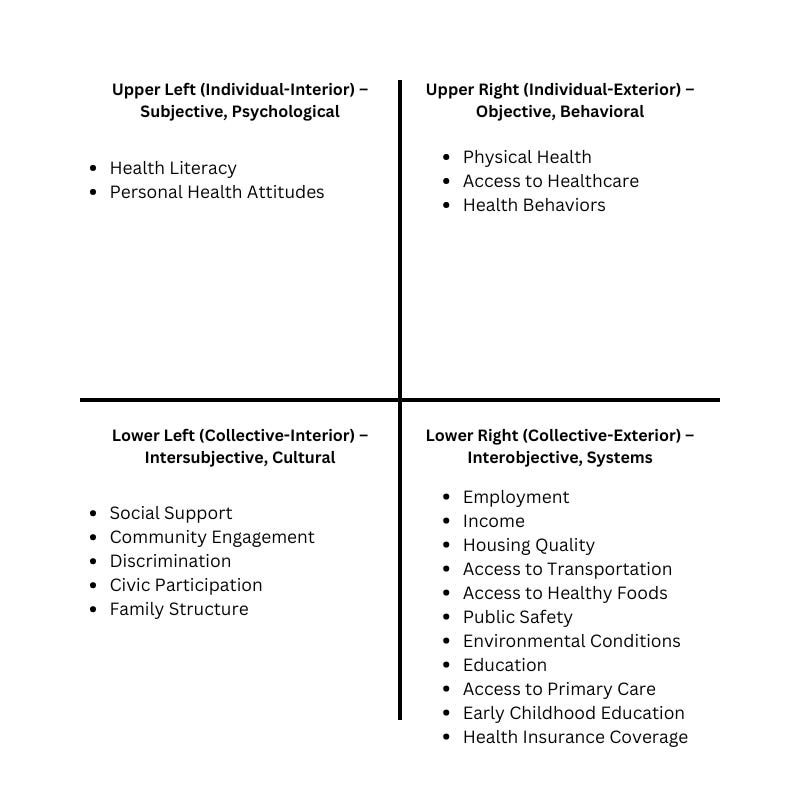

The Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) is a prime example of applying a systems-level lens to address human needs. It recognizes that "health" is not improved by a few interactions but emerges from a multitude of factors on both personal and collective levels. The SDOH includes factors across all four of Ken Wilber's quadrants:

Upper Left (Interior-Individual): Personal inner experiences and self-perception.

Upper Right (Exterior-Individual): Personal physical conditions and actions.

Lower Left (Interior-Collective): Shared cultural beliefs and values.

Lower Right (Exterior-Collective): Societal systems and structures.

Notably, the SDOH is primarily concerned with our collective external needs, focusing on societal systems and structures like healthcare access, education, and economic stability. However, if there is meant to be grounding in a theory of human needs, these systemic or collective needs hardly exist in mainstream psychological views of needs, which tend to emphasize individual desires and motivations.

One conclusion that a Health Department Official might have looking at this systems map is “if we are tasked with improving the overall health of our population, and increasing food security is a requirement for that, perhaps we should partner with or help coordinate food distribution with these community groups?”

And indeed, addressing food security for overall health benefits is something that the National Institute of Health and local health departments do focus on increasingly. This is an example of the SDOH working, of system analysis have real-world impacts.

The SDOH is a great example of applying a system-level lens to addressing human needs, understanding that concepts like “health” are not improved by one or a few interactions, but have a multitude of things underlying them on both the personal and collective level, across both our interior and physical embodiments.

Yet criticism has been made of the SDOH that simply articulating the social needs has done little to make them more accessible. SDOH researchers have become doctors of systems, yet they have few to no prescriptions that actually improve the health of the system.

The Gap Between Individual and Systemic Needs

This raises important questions about the barriers between the self and the collective. Are we overlooking essential aspects of human needs by focusing predominantly on individual needs? Is our reliance on Western psychological theories limiting our understanding of what people genuinely need to thrive?

While we could argue that systemic needs wouldn't show up on individual lists of psychological needs, this separation may be more of a cultural construct than an inherent human truth. Without an objective understanding of underlying human needs and desires, we cannot definitively say which approach is superior. The most likely truth is that they are, from different perspectives and lines of personal development, both true.

Critiques of the SDOH

The SDOH isn't without its limitations. Let’s look at some of the literature criticizing the SDOH. Little of it says that it’s just straight up wrong or unhelpful, most of the challenges arise with its limits, and it's inability to really do much about its diagnoses.

Revisiting the social determinants of health agenda from the global South

Re-politicizing the WHO’s social determinants of health framework

Health in global context; beyond the social determinants of health?

The critiques follow similar lines of analysis. The SDOH, as they’re often used and discussed, are kind of just a list of human needs that emerged from a long lineage of mostly Western analyses about what causes good and bad health. The needs focused on are robust, but don't have any real internal consistency or taxonomical completion — they're kind of just, common sense.

The article The Social Determinants of Health: Time to Re-Think? by Frank et al. poses these critiques:

Emerging Global Issues Challenge the Traditional SDOH Framework: Complex issues like obesity patterns and climate change require a reevaluation of the SDOH.

Difficulties in Translating Theory into Effective Policy: The SDOH often struggles to inform actionable policies that can address systemic problems.

Theoretical and Methodological Shortcomings Limit Impact: Research based on the SDOH may not lead to practical health improvements due to these limitations.

Insufficient Focus on Political Contexts: There is a lack of emphasis on power structures and politics, which are crucial in understanding and addressing health disparities.

Need for Evolution to Address New Complexities: While valuable, the SDOH requires evolution to improve health equity effectively.

These observations highlight the need for a more comprehensive and objective understanding of human needs that transcends cultural biases and limitations. To make real progress, we need to dig deeper and understand the fundamental structure of human systems, and its roots in basic human needs and desires.

In medicine, you need to understand the body at the cellular level, the organ level, and how those organs interact to maintain overall health. Human systems are no different, there are fundamental layers, but we need to identify what those “cells” are when it comes to society — the underlying, unconditioned human needs and desires.

Lessons from the Lexical Hypothesis and Personality Models

To overcome these challenges, we can draw inspiration from how personality psychology has evolved through the lexical hypothesis and the development of models like the Big Five and HEXACO.

The lexical hypothesis is a foundational concept in personality psychology proposing that the most significant and universally relevant personality traits become encoded in a language's lexicon over time. According to this hypothesis, people naturally develop words to describe behaviors and characteristics that are important for social interaction and understanding. By studying these trait-descriptive words, researchers can identify fundamental dimensions of human personality.

FiveThirtyEight.com: Most Personality Quizzes Are Junk Science. Take One That Isn’t.

The Big Five Personality Traits

The Big Five model identifies five broad dimensions of personality:

Openness to Experience: Creativity and appreciation for new experiences.

Conscientiousness: Discipline and goal-oriented behaviors.

Extraversion: Sociability and positive emotionality.

Agreeableness: Compassion and cooperation.

Neuroticism: Emotional instability and tendency toward negative emotions.

This model was developed through an extensive analysis of language, with psychologists compiling adjectives describing personality traits and using factor analysis to identify underlying dimensions.

Limitations and Cultural Biases

While influential, the Big Five model was primarily developed within Western contexts. When applied cross-culturally, certain traits did not align perfectly, indicating that the model might not capture all universal personality dimensions. However, we do not suggest that the Big Five is fundamentally flawed or that alternative models are inherently superior. Rather, we recognize that our understanding is limited and that different cultural contexts may reveal additional dimensions of personality.

The Discovery of Honesty-Humility and the HEXACO Model

Researchers Kibeom Lee and Michael Ashton expanded lexical studies to include diverse languages and cultures. Through cross-cultural analysis, they identified a sixth dimension—Honesty-Humility—which was not adequately captured in the Big Five. This dimension includes traits like sincerity, fairness, modesty, and lack of greed.

The inclusion of Honesty-Humility highlights how cultural values influence the expression and prioritization of personality traits. It underscores the importance of incorporating diverse cultural perspectives to develop more comprehensive models. Again, we are not asserting that this model is more correct but acknowledging that expanding our perspective can reveal aspects previously overlooked.

Methodological Significance

The methodology used in discovering the HEXACO model demonstrates the power of empirical data in challenging and refining existing theories. By expanding research to include non-Western languages and cultures, researchers could identify universal traits that were previously overlooked. This approach aligns with our objective to explore human needs without bias toward any particular cultural framework.

Applying This to Understanding Human Needs

The Interplay of Individual and Collective Needs

Drawing parallels from personality psychology, we can apply similar methodologies to understand human needs. We must recognize the tensions between individual and collective needs and consider how they manifest differently across cultures. Importantly, we do not claim that one perspective is more valid than the other; instead, we acknowledge that without an objective understanding of underlying human needs, we cannot determine which approach is more appropriate.

For instance, in some societies, individual needs for autonomy and self-actualization may be paramount, while in others, collective needs for social harmony and communal well-being take precedence. These differences can lead to misunderstandings and conflicts when creating frameworks intended to address human needs universally. Our aim is to explore these variations without asserting that one is superior.

Metaphysical and Ontological Considerations

Our conception of the self in relation to others profoundly affects how we perceive needs. In collectivist cultures, the self is seen as part of a larger whole, influencing the prioritization of collective needs. In individualistic cultures, personal identity is distinct, emphasizing individual needs.

We recognize that neither perspective is inherently right or wrong. Without an objective understanding of the underlying human organism's needs and desires, we cannot definitively say which conception of the self is more accurate. Our goal is to consider these metaphysical and ontological differences to develop models that accommodate diverse perspectives.

Human Societies as Manifestations of Individual Needs

Human societies are manifestations of individual human needs within specific environmental and cultural contexts. Yet, we lack a universal language to describe these needs beyond the most obvious ones. This gap hinders our ability to develop systems that effectively address fundamental human needs.

By acknowledging that we do not fully understand what we genuinely desire and need, we open the door to exploring these needs without the constraints of cultural biases. Our objective is not to validate one cultural interpretation over another but to seek a deeper, more objective comprehension of human needs.

The Limits of Language in Capturing Human Needs

"The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao."

— Lao Tzu

We often confront the profound realization that language, for all its power, is inherently limited when it comes to expressing the ineffable—the deep, universal human needs that resist precise articulation. As soon as we attempt to name and define these fundamental impulses, we risk confining them within our own contextual frameworks, stripping them of their broader significance.

Wittgenstein encapsulated this dilemma when he said, "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." He recognized that language shapes not just how we communicate, but how we think and perceive reality. Yet, some aspects of human experience—our most profound needs and existential questions—lie beyond the reach of words.

Spiritual traditions have long acknowledged this. Lao Tzu warns that the true Tao cannot be expressed in words. In Judaism, the name of God—Yahweh—is considered ineffable, emphasizing the sacred's indescribable essence. Similarly, Islam discourages depictions of Muhammad to prevent misrepresentation, recognizing that some truths transcend physical portrayal.

So, while we can attempt to map these fundamental needs, we must accept that any specific attributes we assign will inevitably contextualize them, potentially obscuring their universal nature.

E.O. Wilson and Aristotle's Influence

E.O. Wilson, a luminary in evolutionary biology and sociobiology, sought to understand human behavior through the lens of evolution. Interestingly, his work echoes and is influenced by Aristotle's notion of causality, particularly the concept of the Final Cause or Ultimate Cause—the purpose or end for which something exists.

Aristotle proposed four causes to explain why things are the way they are:

Material Cause: What something is made of.

Formal Cause: The form or pattern of something.

Efficient Cause: The agent or process that brings something about.

Final Cause: The ultimate purpose or function of something.

Wilson was particularly interested in the Final Cause—the evolutionary purpose behind behaviors and traits. He posited that to truly understand an adaptation, we must look at its ultimate function in terms of survival and reproduction.

By focusing on the Ultimate Cause, Wilson aimed to uncover the fundamental drivers of human behavior—the deep-seated needs and impulses shaped by evolutionary pressures. His approach was not just about cataloging behaviors but understanding their underlying purposes.

Embedding Ultimate Causes in Language

Here's where our exploration of language comes back into play. If these ultimate causes are universal aspects of human nature, they should be reflected in the languages and cultures around the world. By examining the specific terms and concepts used to describe fundamental needs across different languages, we can begin to identify patterns.

However, as we've acknowledged, directly naming these ineffable needs is fraught with limitations. Instead, by mapping the myriad ways these needs are expressed, we can find that central point—the linguistic centroid—in our high-dimensional semantic space. This point represents the collective understanding embedded in human language, pointing toward the universal Ultimate Cause we're seeking.

This method doesn't claim to pin down the ineffable with exact words. Rather, it respects the diversity of linguistic expressions while acknowledging an underlying commonality—a shared human experience that transcends cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Wittgenstein Revisited

Bringing Wittgenstein back into the conversation, his insights resonate with this approach. He suggested that the meaning of words arises from their use within specific language games—the contexts in which language is employed. By analyzing these varied contexts across cultures, we can begin to perceive the contours of the ineffable needs that language strives to express.

Wittgenstein also acknowledged that some aspects of reality might be beyond linguistic capture. In his earlier work, he famously concluded, "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." Yet, by examining the collective linguistic attempts to express these fundamental needs, we can gain a form of understanding, even if we cannot articulate it precisely.

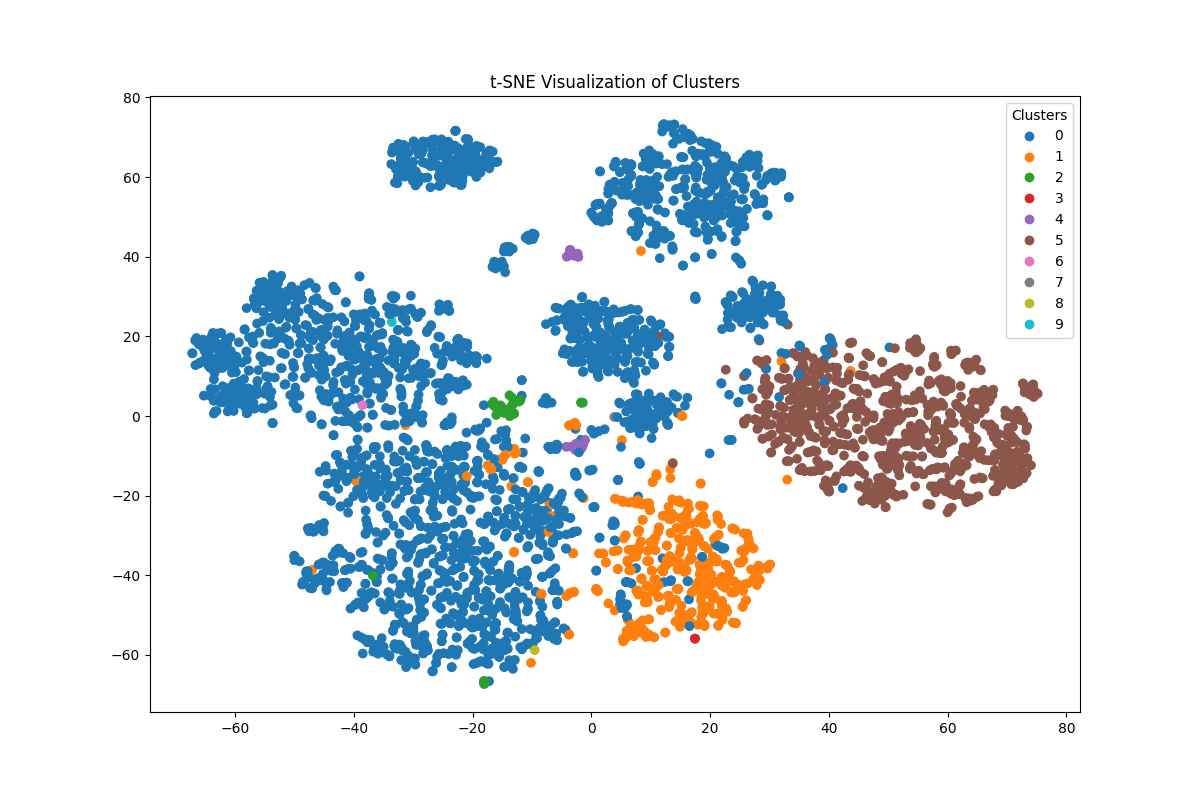

Statistical Centers in High-Dimensional Semantic Vector Space

To overcome the limitations of language, perhaps the truest way to represent universal human needs is not through specific words but as statistical centers in high-dimensional semantic vector space.

In computational linguistics, words and phrases are represented as vectors in a multidimensional space based on their contextual relationships in large corpora of text—a technique known as word embedding. By analyzing these vectors across multiple languages and cultures, we can identify clusters that represent shared concepts or needs that transcend specific linguistic expressions.

This approach allows us to capture nuances beyond language, identifying underlying patterns and commonalities in how different cultures express and prioritize needs. It provides a mathematical and visual representation of human needs that is not confined by the limitations of any single language or cultural framework. Importantly, this method does not favor one cultural perspective over another, aligning with our goal of maintaining objectivity.

Proposed Methodology

To develop a more robust and universally applicable model of human needs, we propose the following methodology:

Data Collection

We will compile a vast list of terms and phrases related to human needs from diverse languages and cultures, ensuring representation from both "Global South" and "Global North" languages, as well as ancient languages like Latin and Ancient Greek. This comprehensive gathering aims to capture the widest possible range of human experiences without bias toward any particular cultural viewpoint.

Addressing Biases

To mitigate semantic biases in AI models trained predominantly on Western texts, we will:

Include Less-Documented Languages and Cultures: Collaborate with linguists and anthropologists to incorporate terms from underrepresented languages.

Collaborate with Native Speakers and Cultural Experts: Ensure accurate translations and contextual understanding.

Use Diverse Data Sources: Incorporate literature, oral histories, and cultural artifacts.

By diversifying our data sources, we aim to minimize cultural biases and avoid privileging one perspective over others.

Quadrant Segmentation

We will use Ken Wilber's quadrant framework to categorize needs:

Interior-Individual (Upper Left): Personal inner experiences.

Interior-Collective (Lower Left): Shared cultural beliefs.

Exterior-Individual (Upper Right): Physical conditions and actions.

Exterior-Collective (Lower Right): Societal systems and structures.

This segmentation helps analyze needs from multiple dimensions, including those systemic or collective needs that traditional psychological theories may overlook. It allows us to explore the interplay between individual and collective needs without asserting that one dimension is more critical than another.

Semantic Embedding and High-Dimensional Mapping

Using AI models, we will map the collected terms into high-dimensional semantic vector space. This allows us to identify relationships between terms across cultures without relying solely on language. By visualizing these relationships, we can uncover patterns and clusters that represent fundamental human needs.

Cluster Analysis and Identification of Statistical Centers

Applying clustering algorithms, we will find groups of related needs. The statistical centers of these clusters represent fundamental needs shared across cultures, beyond specific linguistic expressions. This approach enables us to capture the essence of needs that are universally recognized, even if they are expressed differently.

Importantly, this method does not prioritize any cultural perspective, aligning with our objective of maintaining neutrality and acknowledging that we cannot definitively say which cultural interpretation is more correct.

Validation and Iteration

We will compare our findings with established models like Maslow's hierarchy, Max-Neef's fundamental needs, and the HEXACO traits. Involving experts from anthropology, sociology, and psychology ensures that we refine the model and address ontological differences.

By iteratively refining the model based on feedback and cross-referencing with existing theories, we aim to develop a more comprehensive and universally applicable understanding of human needs. This process acknowledges that our current understanding is limited and that we are open to new insights that challenge existing frameworks.

Enhancing Methodological Robustness

To strengthen our methodology, we will:

Implement Data Quality Assurance: Verify the accuracy and relevance of collected terms, especially from less-documented languages.

Incorporate Multimodal Data Sources: Include non-textual data such as cultural practices, rituals, and art that may express needs beyond words.

Use Iterative Refinement: Employ feedback loops where preliminary findings inform further data collection and analysis.

Ensure Transparency and Reproducibility: Document methodologies and algorithms to allow replication and validation by others.

Final Thoughts

Our goal is to develop a flexible, adaptive model of cultural nourishment that transcends cultural boundaries, acknowledges metaphysical perspectives, bridges individual and collective needs, and incorporates personal development. By utilizing statistical centers in high-dimensional semantic vector space, we aim to capture human needs beyond the limitations of language.

Importantly, we recognize that we do not have an objective understanding of the underlying human organism's needs and desires. Therefore, we cannot claim that any one cultural perspective—be it individualistic or collectivist—is more correct. Our approach is to explore human needs without bias, acknowledging the limitations of our current understanding.

By harnessing AI and linguistic analysis, we seek to build a universally applicable model that helps create systems where everyone's needs are more likely to be met. This approach allows us to move through our ideological apertures and recognize that while our expressions of needs are culturally specific and influenced by metaphysical perspectives, the deeper drives behind them are shared.

Understanding the interplay between individual and collective needs, as well as the profound metaphysical and ontological differences in self-perception, is essential. While we may not have genetic impulses for specific societal constructs like access to healthcare, we have fundamental needs for health and well-being. Structuring society to value and provide such access becomes a way to meet both individual and collective needs without asserting that one approach is inherently superior.

By acknowledging our biases, developmental differences, and the limitations of existing frameworks—including the emphasis on individual needs in mainstream psychology—we can work towards a more inclusive understanding of human needs. This approach challenges us to question underlying assumptions and seek a deeper comprehension of what we genuinely desire and need, without presuming that we have definitive answers.

In our complex world, understanding fundamental human needs is crucial for building societal systems that truly support human thriving. By combining linguistic analysis, AI technology, and interdisciplinary frameworks, we can move beyond the limitations of current models like the SDOH, which focus primarily on collective external needs without fully integrating individual psychological perspectives.

This approach isn't about erasing cultural differences or metaphysical perspectives but about recognizing and honoring the universal human drives that connect us all. We acknowledge that we cannot objectively determine which cultural perspective is more correct regarding individualistic or collectivist interpretations. Instead, we aim to understand human needs in a way that transcends these divisions.

As Wittgenstein suggested, the limits of our language are the limits of our world. To transcend these limits, we must find new ways to represent and understand human needs beyond words. By embracing statistical centers in high-dimensional semantic vector space, we may come closer to capturing the essence of these needs, free from cultural and linguistic constraints.

This model acknowledges that our perceptions of self and other, influenced by culture and personal development, profoundly affect how we understand and meet human needs. Embracing this complexity is essential for creating a world where everyone has the opportunity to thrive. By developing a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of human needs, without bias toward any particular cultural framework, we can design societal systems that are more effective, equitable, and responsive to the diverse realities of human existence.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Introduction

The Need for a Universal Model of Human Needs

Beyond Existing Frameworks: A New Approach

The Complexity of Identifying Human Needs

Psychological Theories of Human Needs

Cultural Biases, not just “Western” ones

Individual vs. Collective Needs

Challenges with Currently Applied Frameworks: The Social Determinants of Health, a Case Study

Understanding the SDOH Framework

The Gap Between Individual and Systemic Needs

Critiques of the SDOH

Lessons from the Lexical Hypothesis and Personality Models

The Big Five Personality Traits

Limitations and Cultural Biases

The Discovery of Honesty-Humility and the HEXACO Model

Methodological Significance

Applying This to Understanding Human Needs

The Interplay of Individual and Collective Needs

Metaphysical and Ontological Considerations

Human Societies as Manifestations of Individual Needs

The Limits of Language in Capturing Human Needs

"The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao"

E.O. Wilson and Aristotle's Influence

Embedding Ultimate Causes in Language

Wittgenstein Revisited

Statistical Centers in High-Dimensional Semantic Vector Space

Proposed Methodology

Data Collection

Addressing Biases

Quadrant Segmentation

Semantic Embedding and High-Dimensional Mapping

Cluster Analysis and Identification of Statistical Centers

Validation and Iteration

Enhancing Methodological Robustness

Final Thoughts

Toward a More Inclusive Understanding of Human Needs

Building Societal Systems for Human Flourishing

The Role of AI and Linguistic Analysis in Understanding Needs

Recognizing the Limits of Cultural Perspectives

Designing Effective and Equitable Societal Systems

Introduction

The quest to understand fundamental human needs is essential for building societal systems that truly support human thriving. I am working on a project that maps complex systems of human interactions, and from this emerges the necessity to categorize, in a taxonomically complete way, all human needs. If we aim to track the activities of public and private institutions to assess how effectively they are working together and achieving their collective goals, we must understand what needs they are fulfilling.

At first glance, this might seem like reinventing the wheel. Existing frameworks can help map interactions between entities like health departments and community food access nonprofits. For instance, we can generate a systems map outlining the interactions between these groups and community members, mediated by the human needs they are fulfilling: economic stability, food security, and healthcare access. This example is robust because many of these factors are framed by the term "Social Determinants of Health" (SDOH), representing elements that research has shown to impact overall health.

However, while these frameworks are helpful, they often lack a deeper understanding of the fundamental human needs that drive behavior across different cultures and contexts. We need a more robust, universally applicable model that transcends cultural biases and captures the essence of what humans need to thrive. Crucially, we aim to approach this without presuming that one cultural perspective—be it individualistic or collectivist—is inherently more correct than another. Our goal is to objectively explore underlying human needs that manifest across various cultural contexts.

The Complexity of Identifying Human Needs

Understanding human needs is inherently complex due to the subjective cultural lenses through which we view the world. Our cultural perspectives shape not only how we express our own needs but also how we interpret the actions and needs of others. This subjectivity creates significant barriers to recognizing that behaviors—even those we deem harmful—often stem from genuine human needs being met in maladaptive ways.

Psychological Theories of Human Needs

Various psychological theories have attempted to outline human needs, providing valuable insights into human motivation and behavior. Among the most influential is Abraham Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, which proposes a five-tier model of human needs, often depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid. The needs range from basic physiological requirements like food and shelter to higher-level psychological needs like esteem and self-actualization.

Another notable theory is Self-Determination Theory by Deci and Ryan, which emphasizes three innate psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These needs are considered essential for psychological growth, integrity, and well-being.

While these theories have contributed significantly to our understanding of human motivation, they often stem from Western cultural perspectives, carrying inherent biases. They tend to emphasize individualism over collectivism, focusing on personal achievement and autonomy. This focus neglects collective needs, which are central in many non-Western cultures that prioritize community well-being and societal harmony.

Cultural Biases, not just “Western” ones

The individualistic orientation of these psychological theories may not account for how needs are experienced and prioritized differently across cultures. For example, in collectivist societies, the sense of self is deeply embedded within the community, and fulfilling collective needs may take precedence over individual desires.

This ontological difference in the conception of the self influences how needs are perceived and met. Our reliance on Western psychological theories may limit our understanding of what people genuinely need to thrive. We must acknowledge that both individualistic and collectivist frameworks offer valuable insights but also have limitations in capturing the full spectrum of human needs.

Individual vs. Collective Needs

The tension between individual and collective needs is a central challenge in developing a comprehensive understanding of human needs. Individual pursuits might conflict with collective well-being, creating tensions not adequately addressed in traditional psychological models. For instance, an individual's desire for personal freedom might clash with societal norms designed to maintain collective order.

However, we are not suggesting that prioritizing individual needs is inherently flawed or that emphasizing collective needs is the solution. Instead, we recognize that without an objective understanding of underlying human needs and desires, we cannot determine which approach is more appropriate. Our goal is to explore these complexities without bias, aiming to understand what we genuinely desire and need as human beings.

Challenges with Currently Applied Frameworks: The Social Determinants of Health, a case study

Understanding the SDOH Framework

The Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) is a prime example of applying a systems-level lens to address human needs. It recognizes that "health" is not improved by a few interactions but emerges from a multitude of factors on both personal and collective levels. The SDOH includes factors across all four of Ken Wilber's quadrants:

Upper Left (Interior-Individual): Personal inner experiences and self-perception.

Upper Right (Exterior-Individual): Personal physical conditions and actions.

Lower Left (Interior-Collective): Shared cultural beliefs and values.

Lower Right (Exterior-Collective): Societal systems and structures.

Notably, the SDOH is primarily concerned with our collective external needs, focusing on societal systems and structures like healthcare access, education, and economic stability. However, if there is meant to be grounding in a theory of human needs, these systemic or collective needs hardly exist in mainstream psychological views of needs, which tend to emphasize individual desires and motivations.

The Gap Between Individual and Systemic Needs

This raises important questions about the barriers between the self and the collective. Are we overlooking essential aspects of human needs by focusing predominantly on individual needs? Is our reliance on Western psychological theories limiting our understanding of what people genuinely need to thrive?

While we could argue that systemic needs wouldn't show up on individual lists of psychological needs, this separation may be more of a cultural construct than an inherent human truth. Without an objective understanding of underlying human needs and desires, we cannot definitively say which approach is superior. The most likely truth is that they are, from different perspectives and lines of personal development, both true.

Critiques of the SDOH

The SDOH isn't without its limitations. Let’s look at some of the literature criticizing the SDOH. Little of it says that it’s just straight up wrong or unhelpful, most of the challenges arise with its limits, and it's inability to really do much about its diagnoses.

Revisiting the social determinants of health agenda from the global South

Re-politicizing the WHO’s social determinants of health framework

Health in global context; beyond the social determinants of health?

The critiques follow similar lines of analysis. The SDOH, as they’re often used and discussed, are kind of just a list of human needs that emerged from a long lineage of mostly Western analyses about what causes good and bad health. The needs focused on are robust, but don't have any real internal consistency or taxonomical completion — they're kind of just, common sense.

The article The Social Determinants of Health: Time to Re-Think? by Frank et al. poses these critiques:

Emerging Global Issues Challenge the Traditional SDOH Framework: Complex issues like obesity patterns and climate change require a reevaluation of the SDOH.

Difficulties in Translating Theory into Effective Policy: The SDOH often struggles to inform actionable policies that can address systemic problems.

Theoretical and Methodological Shortcomings Limit Impact: Research based on the SDOH may not lead to practical health improvements due to these limitations.

Insufficient Focus on Political Contexts: There is a lack of emphasis on power structures and politics, which are crucial in understanding and addressing health disparities.

Need for Evolution to Address New Complexities: While valuable, the SDOH requires evolution to improve health equity effectively.

These observations highlight the need for a more comprehensive and objective understanding of human needs that transcends cultural biases and limitations. To make real progress, we need to dig deeper and understand the fundamental structure of human systems, and its roots in basic human needs and desires.

In medicine, you need to understand the body at the cellular level, the organ level, and how those organs interact to maintain overall health. Human systems are no different, there are fundamental layers, but we need to identify what those “cells” are when it comes to society — the underlying, unconditioned human needs and desires.

Lessons from the Lexical Hypothesis and Personality Models

To overcome these challenges, we can draw inspiration from how personality psychology has evolved through the lexical hypothesis and the development of models like the Big Five and HEXACO.

The lexical hypothesis is a foundational concept in personality psychology proposing that the most significant and universally relevant personality traits become encoded in a language's lexicon over time. According to this hypothesis, people naturally develop words to describe behaviors and characteristics that are important for social interaction and understanding. By studying these trait-descriptive words, researchers can identify fundamental dimensions of human personality.

FiveThirtyEight.com: Most Personality Quizzes Are Junk Science. Take One That Isn’t.

The Big Five Personality Traits

The Big Five model identifies five broad dimensions of personality:

Openness to Experience: Creativity and appreciation for new experiences.

Conscientiousness: Discipline and goal-oriented behaviors.

Extraversion: Sociability and positive emotionality.

Agreeableness: Compassion and cooperation.

Neuroticism: Emotional instability and tendency toward negative emotions.

This model was developed through an extensive analysis of language, with psychologists compiling adjectives describing personality traits and using factor analysis to identify underlying dimensions.

Limitations and Cultural Biases

While influential, the Big Five model was primarily developed within Western contexts. When applied cross-culturally, certain traits did not align perfectly, indicating that the model might not capture all universal personality dimensions. However, we do not suggest that the Big Five is fundamentally flawed or that alternative models are inherently superior. Rather, we recognize that our understanding is limited and that different cultural contexts may reveal additional dimensions of personality.

The Discovery of Honesty-Humility and the HEXACO Model

Researchers Kibeom Lee and Michael Ashton expanded lexical studies to include diverse languages and cultures. Through cross-cultural analysis, they identified a sixth dimension—Honesty-Humility—which was not adequately captured in the Big Five. This dimension includes traits like sincerity, fairness, modesty, and lack of greed.

The inclusion of Honesty-Humility highlights how cultural values influence the expression and prioritization of personality traits. It underscores the importance of incorporating diverse cultural perspectives to develop more comprehensive models. Again, we are not asserting that this model is more correct but acknowledging that expanding our perspective can reveal aspects previously overlooked.

Methodological Significance

The methodology used in discovering the HEXACO model demonstrates the power of empirical data in challenging and refining existing theories. By expanding research to include non-Western languages and cultures, researchers could identify universal traits that were previously overlooked. This approach aligns with our objective to explore human needs without bias toward any particular cultural framework.

Applying This to Understanding Human Needs

The Interplay of Individual and Collective Needs

Drawing parallels from personality psychology, we can apply similar methodologies to understand human needs. We must recognize the tensions between individual and collective needs and consider how they manifest differently across cultures. Importantly, we do not claim that one perspective is more valid than the other; instead, we acknowledge that without an objective understanding of underlying human needs, we cannot determine which approach is more appropriate.

For instance, in some societies, individual needs for autonomy and self-actualization may be paramount, while in others, collective needs for social harmony and communal well-being take precedence. These differences can lead to misunderstandings and conflicts when creating frameworks intended to address human needs universally. Our aim is to explore these variations without asserting that one is superior.

Metaphysical and Ontological Considerations

Our conception of the self in relation to others profoundly affects how we perceive needs. In collectivist cultures, the self is seen as part of a larger whole, influencing the prioritization of collective needs. In individualistic cultures, personal identity is distinct, emphasizing individual needs.

We recognize that neither perspective is inherently right or wrong. Without an objective understanding of the underlying human organism's needs and desires, we cannot definitively say which conception of the self is more accurate. Our goal is to consider these metaphysical and ontological differences to develop models that accommodate diverse perspectives.

Human Societies as Manifestations of Individual Needs

Human societies are manifestations of individual human needs within specific environmental and cultural contexts. Yet, we lack a universal language to describe these needs beyond the most obvious ones. This gap hinders our ability to develop systems that effectively address fundamental human needs.

By acknowledging that we do not fully understand what we genuinely desire and need, we open the door to exploring these needs without the constraints of cultural biases. Our objective is not to validate one cultural interpretation over another but to seek a deeper, more objective comprehension of human needs.

The Limits of Language in Capturing Human Needs

"The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao."

— Lao Tzu

We often confront the profound realization that language, for all its power, is inherently limited when it comes to expressing the ineffable—the deep, universal human needs that resist precise articulation. As soon as we attempt to name and define these fundamental impulses, we risk confining them within our own contextual frameworks, stripping them of their broader significance.

Wittgenstein encapsulated this dilemma when he said, "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." He recognized that language shapes not just how we communicate, but how we think and perceive reality. Yet, some aspects of human experience—our most profound needs and existential questions—lie beyond the reach of words.

Spiritual traditions have long acknowledged this. Lao Tzu warns that the true Tao cannot be expressed in words. In Judaism, the name of God—Yahweh—is considered ineffable, emphasizing the sacred's indescribable essence. Similarly, Islam discourages depictions of Muhammad to prevent misrepresentation, recognizing that some truths transcend physical portrayal.

So, while we can attempt to map these fundamental needs, we must accept that any specific attributes we assign will inevitably contextualize them, potentially obscuring their universal nature.

E.O. Wilson and Aristotle's Influence

E.O. Wilson, a luminary in evolutionary biology and sociobiology, sought to understand human behavior through the lens of evolution. Interestingly, his work echoes and is influenced by Aristotle's notion of causality, particularly the concept of the Final Cause or Ultimate Cause—the purpose or end for which something exists.

Aristotle proposed four causes to explain why things are the way they are:

Material Cause: What something is made of.

Formal Cause: The form or pattern of something.

Efficient Cause: The agent or process that brings something about.

Final Cause: The ultimate purpose or function of something.

Wilson was particularly interested in the Final Cause—the evolutionary purpose behind behaviors and traits. He posited that to truly understand an adaptation, we must look at its ultimate function in terms of survival and reproduction.

By focusing on the Ultimate Cause, Wilson aimed to uncover the fundamental drivers of human behavior—the deep-seated needs and impulses shaped by evolutionary pressures. His approach was not just about cataloging behaviors but understanding their underlying purposes.

Embedding Ultimate Causes in Language

Here's where our exploration of language comes back into play. If these ultimate causes are universal aspects of human nature, they should be reflected in the languages and cultures around the world. By examining the specific terms and concepts used to describe fundamental needs across different languages, we can begin to identify patterns.

However, as we've acknowledged, directly naming these ineffable needs is fraught with limitations. Instead, by mapping the myriad ways these needs are expressed, we can find that central point—the linguistic centroid—in our high-dimensional semantic space. This point represents the collective understanding embedded in human language, pointing toward the universal Ultimate Cause we're seeking.

This method doesn't claim to pin down the ineffable with exact words. Rather, it respects the diversity of linguistic expressions while acknowledging an underlying commonality—a shared human experience that transcends cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Wittgenstein Revisited

Bringing Wittgenstein back into the conversation, his insights resonate with this approach. He suggested that the meaning of words arises from their use within specific language games—the contexts in which language is employed. By analyzing these varied contexts across cultures, we can begin to perceive the contours of the ineffable needs that language strives to express.

Wittgenstein also acknowledged that some aspects of reality might be beyond linguistic capture. In his earlier work, he famously concluded, "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." Yet, by examining the collective linguistic attempts to express these fundamental needs, we can gain a form of understanding, even if we cannot articulate it precisely.

Statistical Centers in High-Dimensional Semantic Vector Space

To overcome the limitations of language, perhaps the truest way to represent universal human needs is not through specific words but as statistical centers in high-dimensional semantic vector space.

In computational linguistics, words and phrases are represented as vectors in a multidimensional space based on their contextual relationships in large corpora of text—a technique known as word embedding. By analyzing these vectors across multiple languages and cultures, we can identify clusters that represent shared concepts or needs that transcend specific linguistic expressions.

This approach allows us to capture nuances beyond language, identifying underlying patterns and commonalities in how different cultures express and prioritize needs. It provides a mathematical and visual representation of human needs that is not confined by the limitations of any single language or cultural framework. Importantly, this method does not favor one cultural perspective over another, aligning with our goal of maintaining objectivity.

Proposed Methodology

To develop a more robust and universally applicable model of human needs, we propose the following methodology:

Data Collection

We will compile a vast list of terms and phrases related to human needs from diverse languages and cultures, ensuring representation from both "Global South" and "Global North" languages, as well as ancient languages like Latin and Ancient Greek. This comprehensive gathering aims to capture the widest possible range of human experiences without bias toward any particular cultural viewpoint.

Addressing Biases

To mitigate semantic biases in AI models trained predominantly on Western texts, we will:

Include Less-Documented Languages and Cultures: Collaborate with linguists and anthropologists to incorporate terms from underrepresented languages.

Collaborate with Native Speakers and Cultural Experts: Ensure accurate translations and contextual understanding.

Use Diverse Data Sources: Incorporate literature, oral histories, and cultural artifacts.

By diversifying our data sources, we aim to minimize cultural biases and avoid privileging one perspective over others.

Quadrant Segmentation

We will use Ken Wilber's quadrant framework to categorize needs:

Interior-Individual (Upper Left): Personal inner experiences.

Interior-Collective (Lower Left): Shared cultural beliefs.

Exterior-Individual (Upper Right): Physical conditions and actions.

Exterior-Collective (Lower Right): Societal systems and structures.

This segmentation helps analyze needs from multiple dimensions, including those systemic or collective needs that traditional psychological theories may overlook. It allows us to explore the interplay between individual and collective needs without asserting that one dimension is more critical than another.

Semantic Embedding and High-Dimensional Mapping

Using AI models, we will map the collected terms into high-dimensional semantic vector space. This allows us to identify relationships between terms across cultures without relying solely on language. By visualizing these relationships, we can uncover patterns and clusters that represent fundamental human needs.

Cluster Analysis and Identification of Statistical Centers

Applying clustering algorithms, we will find groups of related needs. The statistical centers of these clusters represent fundamental needs shared across cultures, beyond specific linguistic expressions. This approach enables us to capture the essence of needs that are universally recognized, even if they are expressed differently.

Importantly, this method does not prioritize any cultural perspective, aligning with our objective of maintaining neutrality and acknowledging that we cannot definitively say which cultural interpretation is more correct.

Validation and Iteration

We will compare our findings with established models like Maslow's hierarchy, Max-Neef's fundamental needs, and the HEXACO traits. Involving experts from anthropology, sociology, and psychology ensures that we refine the model and address ontological differences.

By iteratively refining the model based on feedback and cross-referencing with existing theories, we aim to develop a more comprehensive and universally applicable understanding of human needs. This process acknowledges that our current understanding is limited and that we are open to new insights that challenge existing frameworks.

Enhancing Methodological Robustness

To strengthen our methodology, we will:

Implement Data Quality Assurance: Verify the accuracy and relevance of collected terms, especially from less-documented languages.

Incorporate Multimodal Data Sources: Include non-textual data such as cultural practices, rituals, and art that may express needs beyond words.

Use Iterative Refinement: Employ feedback loops where preliminary findings inform further data collection and analysis.

Ensure Transparency and Reproducibility: Document methodologies and algorithms to allow replication and validation by others.

Final Thoughts

Our goal is to create a flexible model of cultural nourishment that transcends cultural boundaries, bridges individual and collective needs, and adapts to personal development. Using advanced AI analysis, we aim to understand human needs beyond the limits of language.

We recognize our current understanding is limited and that no single cultural perspective—individualistic or collectivist—holds all the answers. Our approach is to explore human needs without bias, using linguistic and AI tools to better understand shared human drives.

By acknowledging the balance between individual and collective needs and the influence of cultural perspectives, we can build systems that address fundamental needs like health and well-being. This requires questioning assumptions and seeking a deeper understanding without presuming definitive answers.

Our approach is not about erasing cultural differences but honoring the universal human drives that connect us. We aim to represent needs beyond language, capturing their essence through statistical patterns in a high-dimensional space. This helps us design more inclusive societal systems that support human thriving, tailored to the complex realities of our world.