NYT and 404 Media: ICE & LPRs, the Intersection of Surveillance And Immigration

Articles in Major Publications Today Unpack the Role of Local Law Enforcement, Surveillance in National & Local Crises of Disappeared Neighbors

Two articles published today by major publications vividly show the intersection of local surveillance, law enforcement, and federal ICE operations.

The first is a NYT piece highlighting the work of The ReMIX and Migrawatch to document what exactly is happening on our city streets between local law enforcement and federal authorities, something that the Governor and DHS cannot give a straight answer to.

The second article is from 404 Media, reporting on revelations about the usage of Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) technology, specifically from the brand FLOCK, a vendor that Nashville has repeatedly considered contracting with. 404 details FLOCK’s routine use in immigration investigations — something never before documented with this level of evidence.

The articles, especially 404’s revelations, show that no surveillance technology is “neutral”, and that these tools and the information sharing infrastructure they allow are designed specifically to prevent any “guardrails” or best practices to stop the use of unwanted behaviors with our data.

What these article prove is what many have long known but some are just waking up to, The Only Way For Metro To Keep Resident Data from the Feds is Not To Have It.

NYT: In Nashville, Volunteers Are Figuring Out How to Counter ICE

404 Media: ICE Taps into Nationwide AI-Enabled Camera Network, Data Shows

Article are reproduced below, please click the links and visit their sites to support their work.

NYT: In Nashville, Volunteers Are Figuring Out How to Counter ICE

By Alex Pena and Emily Cochrane

May 27, 2025, 4:55 a.m. ET

Word spread quickly through Nashville in early May: Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents had been spotted alongside state highway patrol officers along the southern roads where much of the city’s Latino population lives.

The outcry over the nearly 200 immigration-related arrests was fierce in Nashville, a liberal enclave in an otherwise ruby red state. But even as the city’s Democratic mayor, Freddie O’Connell, condemned what he called the operation’s “deep community harm,” it reflected how most Tennessee leaders have embraced President Trump’s crackdown on immigration.

With little official recourse, several Nashville residents and immigration advocacy groups are now acting as unofficial chroniclers of immigration activity. Among them is The ReMIX Tennessee, which set up a hotline for community members to call in and report any sign of immigration enforcement.

On social media, they also circulate warnings about where the Tennessee Highway Patrol and ICE agents have been spotted together. State troopers can make routine traffic stops. Immigration officers legally cannot without probable cause or a warrant, but together, it meant traffic stops could end in immigration arrests.

“Anyone who’s from Nashville knows those areas are densely immigrant, Hispanic, Latino areas,” said Cathy Carrillo, a co-founder of the organization. She added, “if we weren’t out there documenting everything that they were doing, they would be doing double what they were doing, and they would be treating people worse.”

Brian Acuna, an official in ICE’s New Orleans field office, said the operation was focused on “identifying and removing individuals who pose a threat to the safety and security of Tennessee residents.” While some of those detained have not been identified, the agency said that 96 of the 196 arrests had either prior convictions or pending charges.

The Tennessee Highway Patrol “categorically rejects any suggestion that our troopers engage in racial profiling or target individuals based on ethnicity, race, or national origin,” Jason Pack, a spokesman for the department said. Troopers were focused on “observed hazardous driving behavior,” conducting 660 traffic stops and 16 arrests between May 3 and May 13.

“Each stop was lawful, consistent with department policy, and conducted in accordance with the Constitution,” Mr. Pack said.

The agency is now one of more than 600 state and local agencies that have signed a formal agreement with the federal government that allows them to help with immigration enforcement.

Emily Cochrane is a national reporter for The Times covering the American South, based in Nashville.

404 Media: ICE Taps into Nationwide AI-Enabled Camera Network, Data Shows

May 27, 2025 at 9:36 AM

Flock's automatic license plate reader (ALPR) cameras are in more than 5,000 communities around the U.S. Local police are doing lookups in the nationwide system for ICE.

Data from a license plate-scanning tool that is primarily marketed as a surveillance solution for small towns to combat crimes like car jackings or finding missing people is being used by ICE, according to data reviewed by 404 Media. Local police around the country are performing lookups in Flock’s AI-powered automatic license plate reader (ALPR) system for “immigration” related searches and as part of other ICE investigations, giving federal law enforcement side-door access to a tool that it currently does not have a formal contract for.

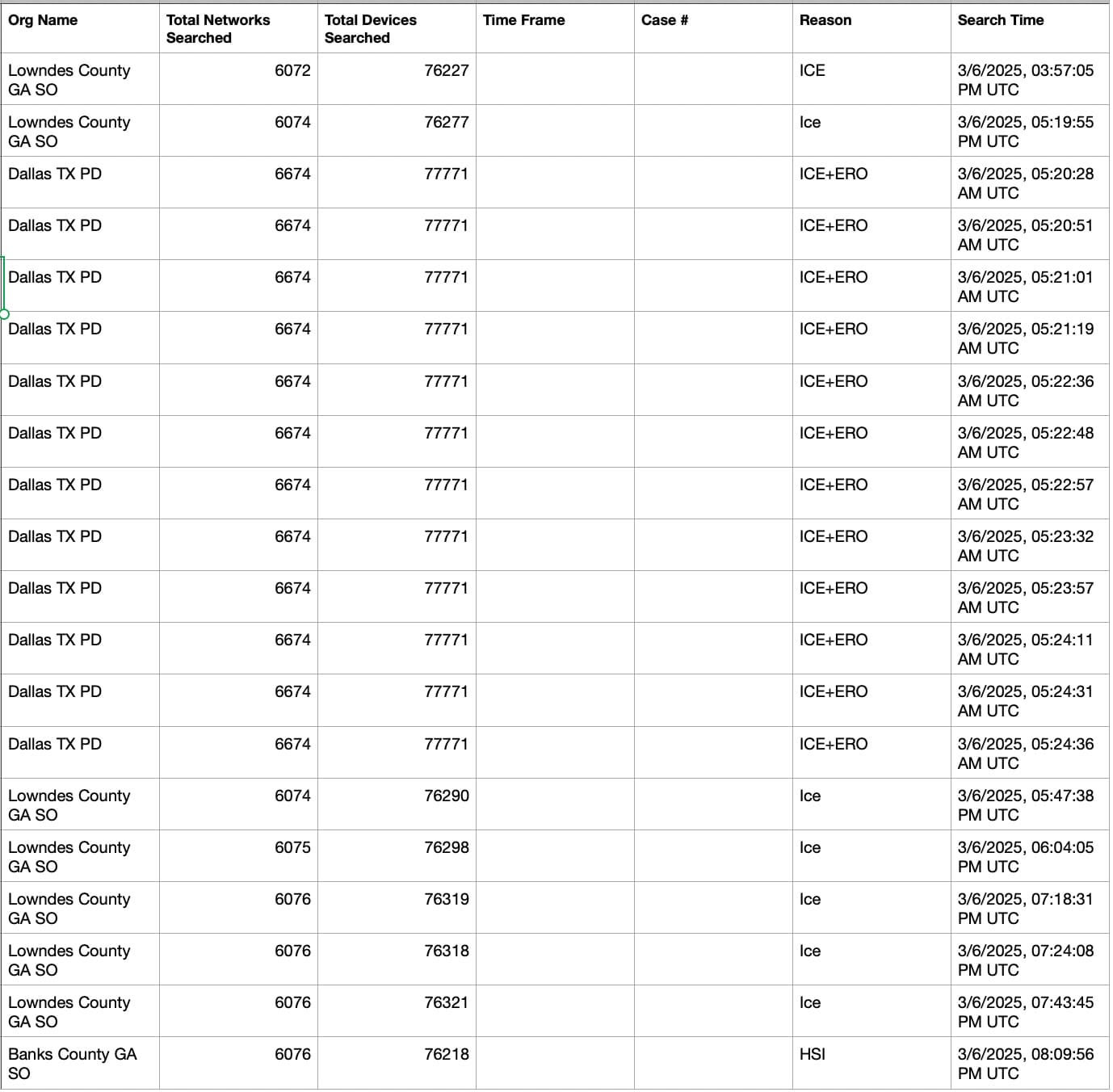

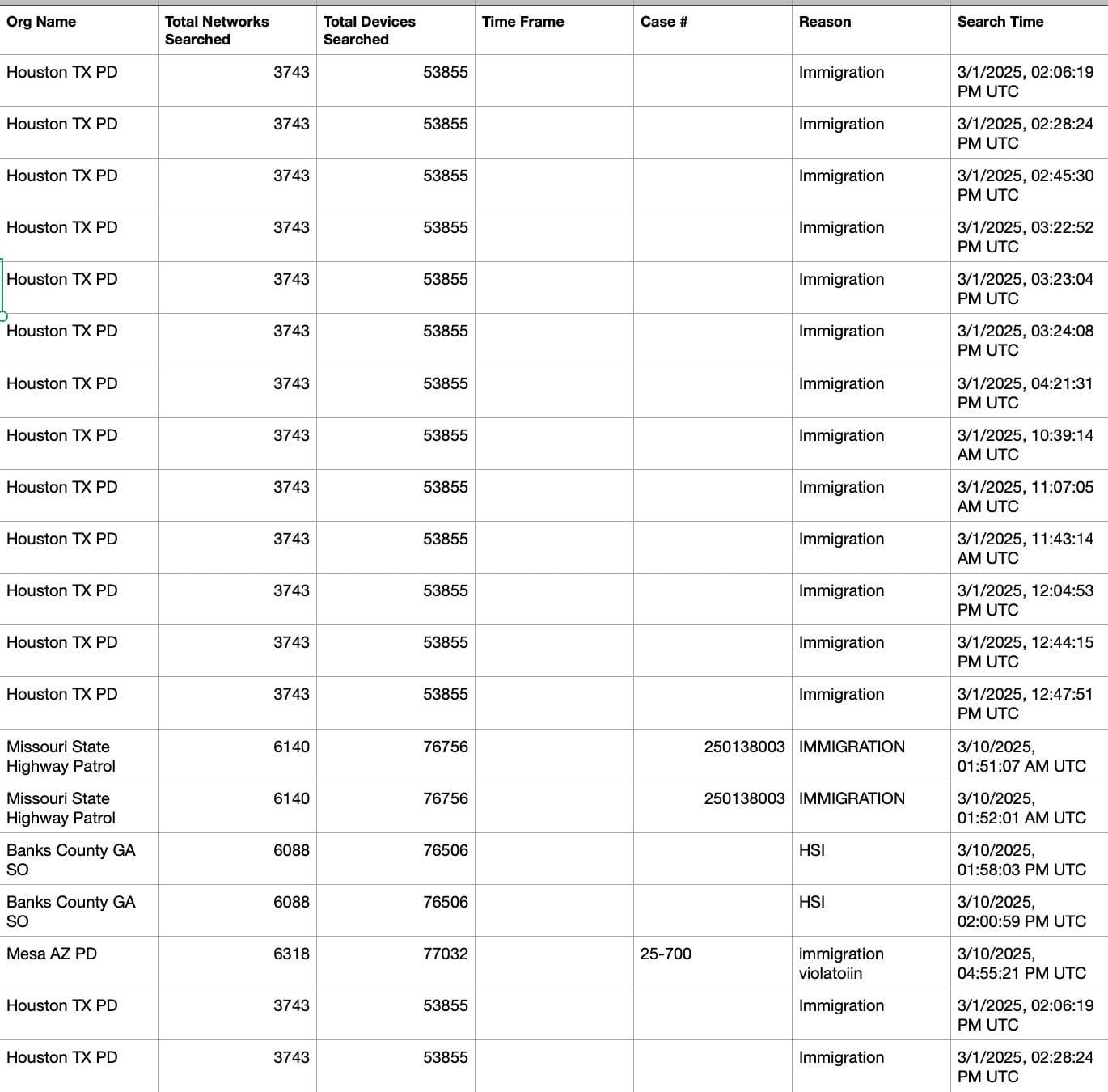

The massive trove of lookup data was obtained by researchers who asked to remain anonymous to avoid potential retaliation and shared with 404 Media. It shows more than 4,000 nation and statewide lookups by local and state police done either at the behest of the federal government or as an “informal” favor to federal law enforcement, or with a potential immigration focus, according to statements from police departments and sheriff offices collected by 404 Media. It shows that, while Flock does not have a contract with ICE, the agency sources data from Flock’s cameras by making requests to local law enforcement. The data reviewed by 404 Media was obtained using a public records request from the Danville, Illinois Police Department, and shows the Flock search logs from police departments around the country.

As part of a Flock search, police have to provide a “reason” they are performing the lookup. In the “reason” field for searches of Danville’s cameras, officers from across the U.S. wrote “immigration,” “ICE,” “ICE+ERO,” which is ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations, the section that focuses on deportations; “illegal immigration,” “ICE WARRANT,” and other immigration-related reasons. Although lookups mentioning ICE occurred across both the Biden and Trump administrations, all of the lookups that explicitly list “immigration” as their reason were made after Trump was inaugurated, according to the data.

Do you know anything else about Flock? We would love to hear from you. Using a non-work device, you can message Jason securely on Signal at jason.404 and Joseph at joseph.404

The Department of Homeland Security does use license plate scanning cameras at the border and has shown great interest in the technology. Immigration advocates have been concerned that ICE could turn to local agencies’ ALPR networks, but this is the first confirmation such data access is happening during Trump’s mass deportation efforts.

“Different law enforcement systems serve different purposes and might be more appropriate for one agency or another. There should be public conversations about what we want different agencies to be able to do,” Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst at the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, told 404 Media. “I assume there’s a fair number of community residents who accept giving police the power to deploy license plate readers to catch a bank robber, who would absolutely gag on the idea that their community’s cameras have become part of a nationwide ICE surveillance infrastructure. And yet if this kind of informal backdoor access to surveillance devices is allowed, then there’s functionally no limits to what systems ICE can tap into with no public oversight or control into what they are tapping into.”

Flock says its ALPR cameras are “trusted by more than 5,000 communities across the country.” These cameras continuously record the plates, color, and brand of vehicles passing in front of them. Law enforcement can then perform searches to see where exactly a vehicle, and by extension person, was at a certain time or map out their movements across a wide date range. Flock is also developing a new product called Nova which will supplement that ALPR data with people lookup tools, data brokers, and data breaches to “jump from LPR [license plate reader] to person,” 404 Media previously revealed. Law enforcement typically do these lookups without a warrant or court order, something which an ongoing lawsuit argues is unconstitutional.

Law enforcement agencies are able to search their own Flock cameras, but also those in other states or even nationwide. A Flock user guide says that national lookups allow “all law enforcement agencies across the country” who are also opted into that setting to search a user’s cameras.

That user guide also says that users can “run a Network Audit to see who has searched your network from any agency in the Flock system.”

The researchers used a public records request to obtain the Danville Police Department’s Network Audit. Because Flock allows police departments to share their cameras’ records across a nation and statewide network of law enforcement agencies, the audit shows whenever Danville’s camera records were searched by police departments around the country.

The data used to report this story shows in real numbers how expansive Flock’s nationwide network of cameras has become. When the Dallas Police Department, for example, performed a series of searches for “ICE+ERO” on March 6, the department wasn’t just searching its own cameras, it was searching 6,674 different individual Flock camera networks composed of 77,771 total devices, the data says. (The Dallas Police Department declined to comment on its searches).

Searches across Danville’s Flock cameras came from other agencies in Illinois, such as the Chicago Police Department. The data also includes state and local law enforcement agencies from all over the country, such as sheriff offices and police departments in Florida, Arkansas, Louisiana, South Carolina, Virginia, Arizona, and Texas. The Florida Highway Patrol and Missouri State Highway Patrol are also included in the data. The network audit stretches from June 1, 2024 to May 5, 2025 and contains millions of total searches. The researchers then narrowed that data to the more than 4,000 searches that contained immigration keywords in the “reason” field.

“I can't speak for the company as a whole, but I was unaware that Flock's tools were being used by local departments in collaboration with ICE. I'm disappointed, but not surprised,” a Flock source said. 404 Media granted the source anonymity as they were not permitted to speak to the press. “It's really important that people understand how this tech—which they pay for with tax dollars—is used, since ultimately it's up to state and local governments to draw the boundaries of fair use by law enforcement.”

There are some caveats with the data. Many of the entries list the lookup reason as HSI, and HSI has a broad criminal investigative mandate beyond immigration enforcement, meaning that the police are helping a division of ICE but may not be using Flock specifically for immigration enforcement. Some law enforcement agencies told 404 Media they are not engaging in immigration enforcement despite the reason for the Flock lookup saying “immigration.”

A Missouri State Highway Patrol spokesperson told 404 Media that although the listed reason for using Flock was “immigration,” the lookup “was related to a traffic stop with indicators of possible human trafficking.” The spokesperson added “We are in the process of obtaining the training and creating the applicable policies” for immigration enforcement. Other agencies that listed “immigration” as the reason for the lookup did not respond to a request for comment.

The Trump administration has made a point of encouraging state and local police departments, which do not normally have authority to enforce immigration laws, to apply for a program called 287(g), which allows ICE to “delegate” the enforcement of immigration laws to local police. A January executive order issued by Trump instructs DHS and ICE “to authorize State and local law enforcement officials, as the Secretary of Homeland Security determines are qualified and appropriate, to perform the functions of immigration officers in relation to the investigation, apprehension, or detention of aliens in the United States.”

It is particularly notable that the data in question came from an Illinois police department, because Illinois is one of the few states that specifically bans the use of ALPR data for immigration enforcement. Illinois-based police departments that ran searches shown in the data insisted that the searches were for criminal cases or were not specifically for immigration enforcement purposes.

“The chart [data] provided does not indicate that Danville PD is searching Flock LPR data or acting for another municipal, county, or state LE agency, nor ICE regarding immigration,” Danville’s police chief Chris Yates told 404 Media. “As required by the State of Illinois we ensure that we will not use LPR data or enforce a law or relate a person’s immigration status.” Yates did not respond to follow up questions about why the Flock audit showed searches for immigration-related reasons from other agencies around the country.

“Long-story-short, what is being alleged is not happening,” Danville’s mayor, Rickey Williams Jr added.

But Danville’s own data is showing that these searches by other police departments are in fact happening, and 404 Media confirmed the details of several searches with the departments that performed the search. The police departments we got details from said that sometimes searches for federal agencies are “informal,” and sometimes they are part of a specific investigation. What is clear, however, is that ICE and HSI have gained side-door access to a tool that they do not formally have access to.

Andrew Perley, the deputy chief of the Village of Glencoe, Illinois police department, told 404 Media that a specific search “was not related to an investigation involving immigration status. The inquiry was an informal request from Homeland Security Investigations into a criminal matter aside from immigration.” Ryan Glew of Evanston, Illinois police department, told 404 Media that one of their specific searches was because “We were assisting Homeland Security in the apprehension of a wanted subject. The subject was part of a nationwide retail theft ring that was responsible for millions of dollars from stores across the country. The queries were not immigration-related.”

Other police departments in Illinois we spoke to said that some of the searches were done to “assist” federal law enforcement, or that the searches were done by one of their “task force officers,” who are local police that are embedded with federal units. Mike Yott, the police chief of Palos Heights, Illinois, said that, due to Illinois law, his department does not do immigration enforcement. But he said that he did not know what a search performed by one of its department’s task force officers embedded with the Drug Enforcement Administration was for, even though it read “immigration violation.”

“Based on the limited information on the report, the coding/wording may be poor and the use of Flock may be part of a narcotics investigation or a fugitive status warrant, which does on occasion involve people with various immigration statuses,” Yott said.

The fact that police almost never get a warrant to perform a Flock search means that there is not as much oversight into its use, which leads to local police either formally or informally helping the feds by doing lookups.

“Law enforcement really likes license plate readers because of the lack of restrictions on that data. They don’t feel like they need a warrant. Oftentimes there are no restrictions whatsoever on what they search,” Dave Maass, who studies border technology at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told 404 Media. “It might be totally true that some of these searches are for people who have warrants or who are wanted for criminal activity. They might be looking for a terrorist, who knows. But that’s kind of the point—we don’t know.”

Flock said in a statement that “We are committed to ensuring every customer can leverage technology in a way that reflects their values, and support democratically-authorized governing bodies to determine what that means for their community.”

“All Flock customers own and control 100% of the data collected by their Flock systems and choose who to share data with. The tools are fully auditable, indefinitely saving usage reports so command staff or city leadership has full insight into the use of the products. The network audit logs are an example of this auditing-by-design approach,” the statement continued. The company said its tools have helped law enforcement locate more than 1,000 missing persons.

“We work with local governments across the country to adopt best practices on LPR policies, including robust auditing requirements. Flock’s platform requires double opt-in for agencies to share data amongst each other—we recommend every agency adopt a strong LPR policy, conduct regular audits, and be thoughtful about how and with whom they share data,” the statement continued.

“What is incredibly frustrating is that Flock in particular in Illinois marketed themselves to a bunch of communities in the suburbs and in Central Illinois as a device that would be critical to combatting an uptick in crime, violent crime, gun violence. But this is really a national system of data once you start collecting this, whether it’s Bloomington or Springfield or Danville, you start looping together those networks,” Edwin Yohnka, director of communications and public policy for ACLU Illinois, told 404 Media. “So it is incredibly troubling to see this list of places from around the country who are performing these searches of Illinois cameras.”

DHS did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

About the authors

Jason is a cofounder of 404 Media. He was previously the editor-in-chief of Motherboard. He loves the Freedom of Information Act and surfing.

Joseph is an award-winning investigative journalist focused on generating impact. His work has triggered hundreds of millions of dollars worth of fines, shut down tech companies, and much more.