Downtown Nashville's Self-Made Privacy Crisis

The surveillance product that Downtown businesses are cajoling the Mayor to implement could turn those businesses "into the product." I know it's possible, because I used to do it.

Before I worked in the Nashville Mayor’s Office of Community Safety, I was the Global Manager of Webinar Services for a $100M live-streaming and on-demand corporate video platform. Our clients cared about the security of their video content. A lot.

Our platform was often used by Fortune 100 firms like JP Morgan, CitiBank, HSBC, Oracle, and BNY Mellon to send private videos, both live streaming and on-demand, to our subscribers who had exclusive, sometimes NDA-bound, permission to view this content.

These were Whales of clients, and boy! did our sales execs and technical teams have to work overtime to sign or renew them. Every computer server their data touched had to be detailed, every security protocol we used had to be documented, every sub-contractor that could possibly access their data (even if they weren’t legally supposed to) had to be disclosed.

I’m telling you this because while I’ve been looking at how Metro has been discussing the safety and trustworthiness of the surveillance system called Fusus from the Axon corporation, its been alarming to me how little due diligence has been done on this product, and the company that sells it.

Metro officials have been using truly Boomerific metaphors to explain Fusus, saying things like: “It’s just a little man, going down a wire!” (A real thing that happened.)

But that makes it sound like Fusus is just a one way, “two node” hardline connection from Public Cameras to MNPD. They talk about “Fusus” as if it’s a static piece of equipment that more or less just converts a camera’s output into something that can be sent securely over the internet. Products like that exist. I used them for years. And maybe that’s what Metro officials actually think Fusus is. But it’s not.

Without the right provisions in place, provisions that local, state, and even federal law probably do not have the teeth to implement (and now less than ever), the risk posed by mass surveillance controlled by for-profit corporations is just as high for corporate executives and intellectual property owners as for the trans teen who is worried about being arrested for wearing “drag”, or the Ukranian immigrant who lost their refugee status because Trump is mad as Zelinsky.

As someone whose job it actually was to send video securely over the internet, and to store and process it (and data generated from it) in a manner that it could be viewed either live or after the fact, someone who worked at a firm that performed virtually the exact same technical role as what Axon is selling Metro — Metro officials either have no idea what they’re buying, or are doing that thing where you don’t tell the truth on purpose

Which is great news for Axon. At my old company, it was great when clients signed up for stuff they didn’t understand or didn’t pick a fight over the terms and conditionss. It meant they were hardly going to use what they bought and we could still charge them for it. It meant that b-roll we purchased for their videos could be used for other clients. But I think the consequences are a lot more dire for Nashville, though, if we don’t read our contracts.

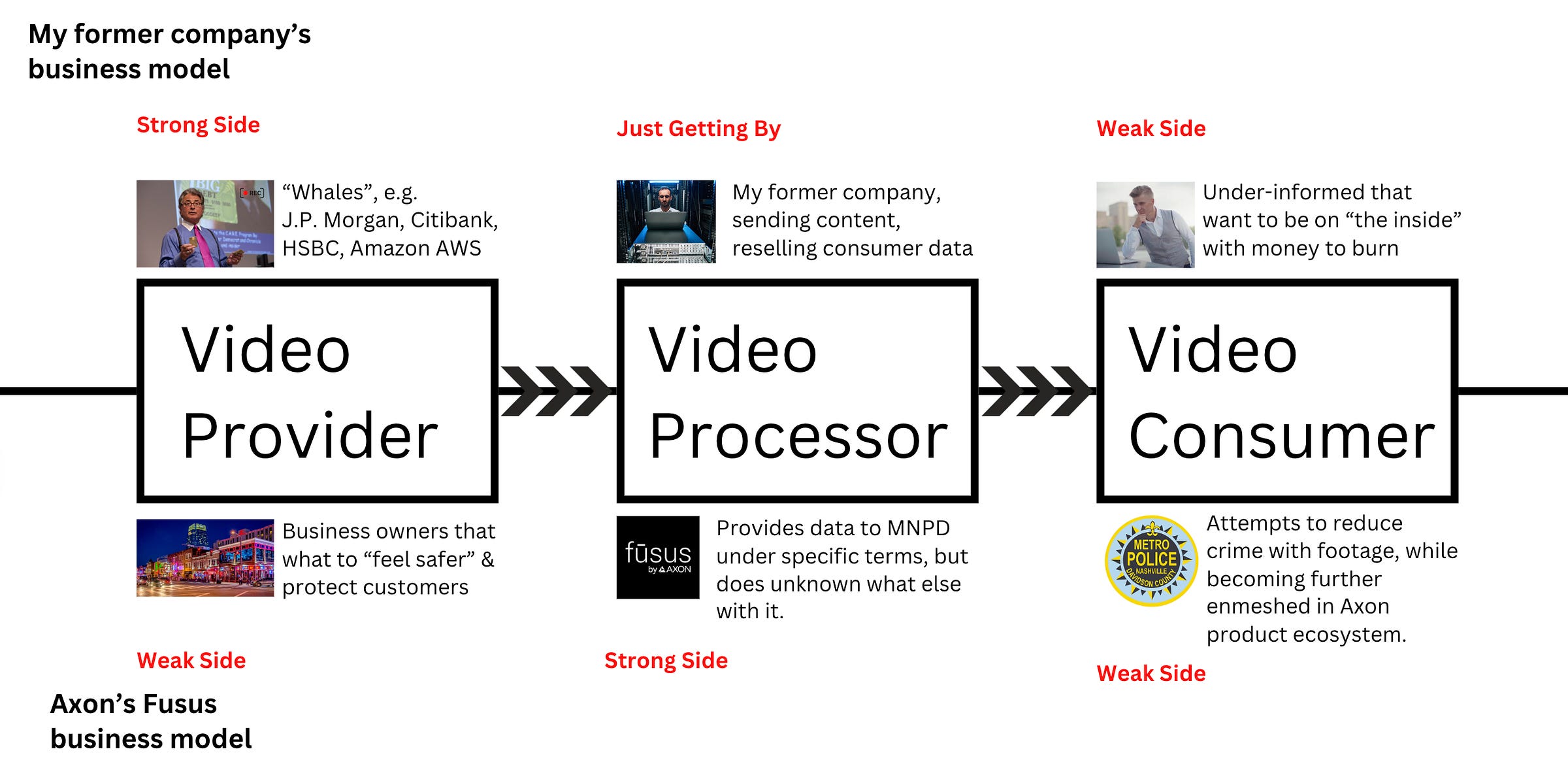

Similar to the role my company was performing in NYC, Axon is the middleman, the “Video Processor” in this arrangement.

In both of our business models, the flow-of-data goes from the Video Provider, to the Video Processor, and ultimately to the Video Consumer. But there are some important differences between the arrangement we had, and what Axon has.

In our business model, the people providing the footage were on the Strong Side of the arrangement — they had the most power. We needed their business, the consumers needed their content. So we would all bend over backwards to do things the way the Content Provider wanted. And that meant it was going to be secure, stay within the flow of data they wanted, and the consequences for breaking these terms meant that all the content was instantly shut off if the Content Provider was displeased.

The incentives were in place and the power distributed in a way that keeping the video content genuinely private, by the terms and definitions of the providers of the video, was in the best interest of everyone.

We were somewhere in the middle. We didn’t need the video consumers as much as they needed us, so we could make the consumers provide us things like their contact info that we could sell to third parties. It also meant that we weren’t completely weak in the equation — our giant whale clients brought high-value video consumers to our platform, which meant we could sell their contact information and the surveillance data we had about what corporate videos they were interested in for a lot of money.

On one level, this was just a way for people to share information. To help folks make smart investing choices and to help build deep prosperity across the economy. It was a win-win-win situation for us all.

Only kidding. The big data industry is ANYTHING but win-win-win. Any time you’re thinking, “Wow, I’m really getting a lot of value from this product without having to pay very much!” You are, in fact, the product. And don’t think that just because we are paying for someone to take our data, that it makes us the customer. That just makes us even bigger rubes.

I first raised my concerns about Axon on March 3rd, noting that Metro was moving toward passage of a contract, but no one seemed to have access to what the business’s side of the T&Cs were going to be.

Metro has not produced any indication about what they think the terms between Axon and residents would be.

Axon hasn’t answered questions on this topic either.

I believe they haven’t answered this because I am, to my knowledge, the first person who asked them this — on an email chain with every member of Metro Council visibly copied.

No response yet as of publication.

You don’t need to understand the mechanics of the data aggregation business model I was a part of to understand Fusus or other data aggregation tools. What’s important is to get the gist though that arrangements like this always have someone on the losing side.

With us the deal was, more or less, big banks were securely sending out secure, “exclusive” video content to try to get people to give them their money — and we’d use the email lists of the Consumers they sent to us to spy on those consumer’s activities on our platform (with them fulling agreeing to this in the T&Cs virtually none of them read) and then we’d resell that contact info and data about their interests to other firms that would also tried to take their money.

“The Circle of Life (Reprise)” plays. Roll credits.

If this sounds gross and surprising to you, congratulations, I’m jealous you didn’t know about this already. But you should know that this is how a lot of the profit is made using data on the internet. Internet data brokering is an ever-evolving ratking-like ecosystem that leverages “exclusivity” and surveillance to turn a profit for everyone BUT the person on the weakest side of the arrangement — the one being surveilled.

Surveillance is a core part of the internet economy, and it comes in two forms: individualized and aggregate.

I worked in demand generation marketing where it was important to get the contact info and activity history of specific, high-profile people. This is individualized version of marketing, where you want to know precisely who you’re dealing with, and it more closely resembles the type of surveillance we see with companies like Palantir and Axon. It’s not so useful to tell that police departments that crimes are being committed by some people as to be able to say “these people are committing those crimes.”

I’m seeing a lot of overlap in the theories and practices in the increasingly big data, gamified version of law enforcement surveillance culture to the demand-generation marketing I cut my teeth on. I am very confident that the same theories and practices are being applied to both.

To illustrate how small the data aggregation and resell business is, here is Marc Palmieri, Sr. Product Specialist of Axon Fleet (a video recording system for police cars), co-hosting a webinar on the platform I used to work at.

If I still worked there, I would have been overseeing their recording and helping Axon get their product pitches into the inboxes of Police Chiefs and City Council Members across America — giving those officials the ammo to endorse Axon products and refute resident concerns. Product marketing is as much about answering objections to your products as it is about steering the conversation toward the questions you want the consumer to be asking.

If I were Axon a marketing executive, I’d be sure potential clients, and the regions they represented, were thoroughly invested in questions like: “What can my police force do and not do with this data?” because that’s something they can, in theory, control (and not actually hurt my business very much). But I’d be sure the conversation never even got around to asking things like: “What might Axon do with this data?”

If I were a good senior sales executive at Axon, I’d know that the public’s capacity for outrage is a limited resource, and my experience from doing this from city to city might tell me that it’s important to let the outrage flow where you want it to.

But at the end of the day, whether it’s body cameras, LPRs, Fleet recording devices, Evidence.com, I’d know that my company Axon has cities and police departments over a barrel.

Reuters: Second US town sues Taser-maker Axon for antitrust violations

This brings us back to what may or may not be Axon’s business model with Fusus. I genuinely don’t know what they do with the data they collect besides give it to local law enforcement, but I would be shocked if it was nothing. You don't get to a $50B market cap by turning money down over something as pollyanna as “the constitutional right to privacy.” Plus if you can get people to willingly agree to give up their privacy and the privacy of their customers — and even pay you to take it from them. That’s a win-win-win (for Axon).

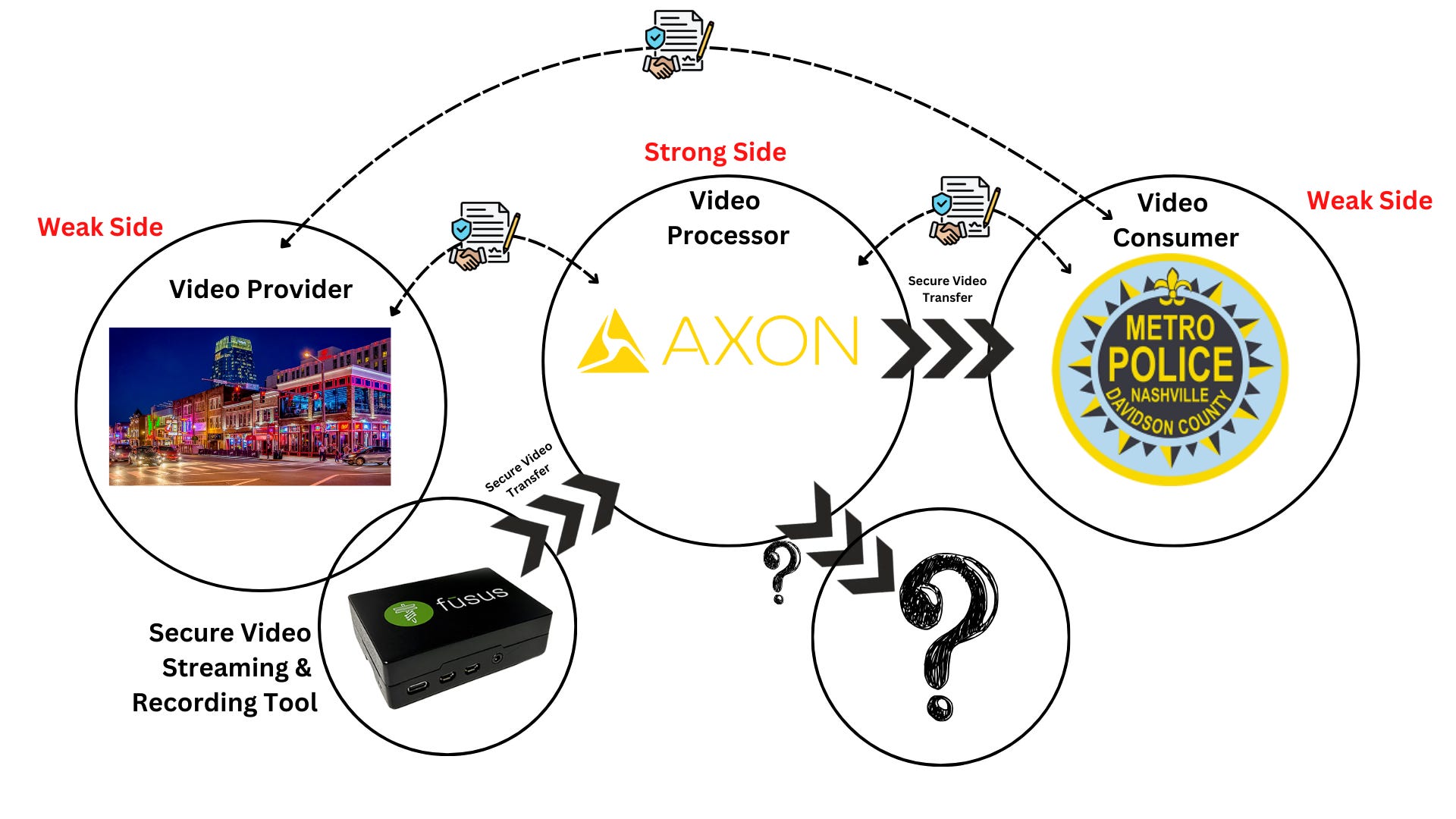

Axon’s business model with Fusus, from what I’ve put together, on one level is the exact same in terms of data transfer. The content starts at the Video Provider (Donor Cameras), moves through the Secure Streaming and recording tool (Fusus), to the Video Processor (Axon), and finally to the end video consumer (MNPD).

There is no reason I can see why the limits Metro puts on itself have any bearing on Axon in terms of what they can collect from Donor cameras and do with it. Perhaps Metro could set limits on the T&Cs it is allowed to ask camera donors to sign if those donors are to be allowed in Metro’s system. Answering these questions, though, would require someone with power caring about these things.

One thing that’s different with Axon’s model from ours is that the Video Provider is the Weak Side of their arrangement. Businesses that want to make their city safer by opting into Fusus can take the terms Axon gives them or walk — terms that have not, to my knowledge (and send them to me if I’m wrong!) been made public.

If one business opts out of Fusus because they don’t like the T&Cs it will not break the bank for a $50B company. In my old business model, if the Video Provider thought there was the slightest chance we would resell their content, passively allow access to a competitor, or not implement security protocols that could protect it from hacking, they’d pack up and go to the next vendor down the street.

Donor Camera providers in Nashville, even the biggest ones in the city or the Chamber of Commerce itself, don’t have this leverage to negotiate terms for data sharing if Axon doesn’t want to play ball. It would be like bringing a taser to a gunfight.

The Unknown Strong Side of a Fusus System

In my old company’s business model, the video providers were on the strong side of the arrangement. We followed privacy and security protocols to keep their video content safe, not out of ethics or because of US data privacy laws (because those basically do not exist) but because we were economically incentivized to do so. The video providers would take their webinars and go to that ugly, ugly platform On24 if we violated their trust.

The consumers of the videos were basically the rubes, the marks. The video producers (big banks, tech firms) were pitching them to give them boatloads of cash, and we were taking the consumers’ contact info and online behavior we’d surveilled and sold it to more people that would try to extract data from them.

But with Axon’s business model with Fusus, the video providers are not the strong side of the arrangement. So you might think that that means that Metro and MNPD is the strong side — that the arrangement is just flipped. But they’re not. Axon’s the strong side. By a mile.

Axon is basically the sole provider of body cams and other “essential” law enforcement equipment. A city making a deal with them is like a small retailer making a deal with Amazon. It’s not so much of deal as it is an offer you can’t refuse.

Like any good, powerful product and service provider, Axon gets their customers into their ecosystem and makes it hard to leave. A thing I’ve heard Senior Sales Leaders rail about is that you need to make customers sticky. You need the products they buy to be diverse, they need to see your logo everywhere they look — not so much for branding purposes but to make them aware that it would be a real goddamn headache to switch to another provider.

“Sure,” their customer service rep would say if he worked for me (and I wanted to be the biggest law enforcement data broker in the world), “but that actually product is actually integrated with the evidence hub and shot spotter tool. If you remove that aspect of it, you would lose the cloud data storage platform and all your evidence will be erased… but if that’s what you want to do, no problem!”

Like the donor camera providers, MNPD and Metro are also on the weak side of this arrangement with Axon — they have virtually no leverage besides just not buying things.

To fulfill the task that Downtown Nashville has required of them, Metro is going to be told to sign a contract for X-Years at X-Price, even if that means compromising the privacy of Nashville businesses and residents and giving it to unknown third parties they can’t regulate with Metro Ordinances or one-sided contracts.

The First Rule of Big Data: If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.

The Second Rule of Big Data: Paying for someone to take your data means you’re not the one profiting off of it.

So, that makes Axon the Strong Side in this arrangement. Which is a precarious place to be if you’re MNPD or a donor camera provider that expects some level of control and insight into what’s happening with the video footage you’re giving this weapons company. But since Axon has the power in the situation, they very well could (and I must say for both intellectual honesty AND liability reasons that I have no evidence currently that they do this) provide our video content or data generated from it to other 3rd parties.

Under various information security laws, agencies like the Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the Department of Justice have conditions by which they can demand access to this data from vendors like Axon.

But what’s more, Axon is fully entitled to sell the footage provided to them by privately owned cameras, or AI generated content they create from this footage — assuming their contract does not say otherwise. And whats more, the definition of what is the donor camera’s original content is ever more increasingly obscure in today’s era of big data. Perhaps the client owns the video footage. But what about an AI enhanced video derived from it that has object recognition AI algorithms in it, something Axon advertises Fusus can do?

Governments Are Completely Clueless about AI

Let’s say it’s important for someone to feel comfortable partaking in being a Fusus donor camera provider to know that they own their footage so it can’t be misused or abused. I would call that person reasonable.

But the definition of what footage is in the modern landscape of AI generated content is changing by the moment. Meanwhile in government, today’s Gerontocracy in charge of regulating it on a Federal and Local level makes Fmr. Senator Ted Stevens, the “the internet is a series of tubes” guy, look like Tank from The Matrix.

So even if the original, unprocessed video footage remains under the copyright of the donor camera: (1) what’s to stop Axon from sharing it with third parties for disclosed or undisclosed “emergency” reasons as defined by themselves or those third parties; (2) what, if any (probably none) ownership can the donor claim for content derived from their footage?

“Processing” a video though AI image detection algorithms could not only “wash” the ownership claim of the camera provider, but potentially increase its worth to people that may want to do things as banal as observe consumer shopping behaviors, or as open-ended and Skynet-esque as “utiliz[ing] artificial intelligence to rapidly search video provided to the system by users in order to mitigate criminal activity” —a line taken directly from the MNPD endorsed connectmetronashville.org hosted and maintained by Axon.

If we take the official Nashville.gov website about Fusus at its word and trust that donor camera providers “own” their footage (something not stated on the Axon-hosted site), what do we mean by “footage”? If we look at the set of images below, we’d say the original footage is (a). But what about derived content? Would they own (b), the same image but with AI object detection added on top of it? We might argue that because clearly it’s the same content, just with little boxes and labels on top of it.

But what about (c) or (d), true abstractions that are referencing the conceptual entities within the video more than being the video itself?

And what about a true abstraction, a textual analysis of what’s in the video, like when I run image (a) through ChatGPT and ask it to do a “threat analysis” on these three men.

The image depicts three young men indoors, engaging in what appears to be a playful but exaggerated display of confidence and style. From a threat analysis perspective, there are no immediate indications of danger, but certain behaviors may warrant contextual evaluation. The individuals are wearing sunglasses indoors, which can obscure eye contact and facial expressions, potentially making it harder to assess intent. The individual on the right is lifting his shirt slightly, which could be a non-verbal dominance display, though there are no visible weapons or overt signs of aggression. Their postures and stances suggest they are performing for the camera rather than displaying hostile intent. The environment appears to be a residential setting with no obvious threats, hazardous objects, or concerning background elements. Overall, the image does not indicate any imminent risk but could be assessed further based on situational context and intent.

Would a donor camera provider get to claim any ownership over this content? That seems extraordinarily unlikely.

The most that government and citizens seem to be able to understand and try to mitigate against the is danger of “facial image recognition”. Axon as a whole has stated that facial recognition is not being used on any of their platforms.

Our privacy concerns over AI should never be so specific as “facial recognition technology is the problem. “Facial Recognition Technology” as a concept can be pigeonholed with legalese and AI researcher jargon to mean a very specific set of tools, and banning that will just cause people to change the terms and specific processes.

The AI space is going to be, forever, a whack-a-mole as long as we try to protect privacy by defining things we don’t want by the way they work today or what the industry term is for them.

It’s exactly what happens with “designer drugs” like “bath salts”. Because of the way our drug enforcement works, where we ban specific molecular structures of drugs only after public health crises demonstrate they are unsafe for public consumption, the “designers” of these drugs tweak a single molecule, and they can now be sold at gas stations and truck stops again as “supplements.”

If our fear is not the specific capacity of doing “facial recognition” on videos of the public, but rather we are focused on banning technology that can autonomously detect who we are — we see facial recognition is just one of many things you can slap on a video in real time or after the fact and do.

This article details how surveillance systems can skirt bans on things like facial recognition but still tag and track specific individuals based on their visible attributes and across time and space.

We can tell firms like Axon they’re not allowed to use facial recognition, and they’ll say “aw, damn. You know, it’s really your loss, we can do it safely. But totally, we get it, no problem.”

But I find it highly unlikely a good product manager doesn’t have a slightly tweaked, technically not facia recognition technology up and running that is able to identify through automation someone uniquely from everyone else in a wide data set and cross reference them to public information sets and get their personal info.

Or honestly, firms might just use it anyway and say they’re not. Because like most of the designer drugs manufacturing out there, there’s just not enough energy to stop it.

But because we don’t know their terms and conditions for their relationship with businesses giving donor camera footage, we don’t even know what they’re claiming they have the right to do with data.

We ultimately don’t know what the arrangements Axon has and other entities. We don’t know what they’re doing, besides things that are public information, like that they’ve had $14M+ of contracts with the Department of Homeland Security since 2020 — we actually don’t know who might be the ultimate strong side of the arrangement. It’s possible Axon and firms like them are not the power brokers in this equation but are serving the call of a higher master that will never be disclosed to us.

Would Axon allow some data scraping by government agencies that can make or break them with a single contract? Would they be above selling our surveillance data to a data broker if they were having a really bad quarter?

I don’t know the answer to this. But it really seems like no one else is asking Axon this.

And if these things were the case, there would not, by my understanding (and I have given Metro and Axon ample opportunity to correct me if I’m wrong), be anything that Metro or TN, or the US gov could do to stop this if the terms and conditions with the donor camera providers allow for this. They have no real power, except to not sign Metro Nashville up for this in the first place.

This is why it’s very troubling to me that these terms and conditions are nowhere to be found. Or if Metro or Axon has them, it’s very weird they’re sitting on them.

All of us business girlies know that when there’s a deal between three parties, there’s more than just two sides of that deal.

Downtown seems to think that Metro, after taking the warm handoff with Axon, went and did their due diligence and hammered out all the find details. “The only task now to get it through Council,” the hallway whisperers are whispering, “is to get those trans rights activists and immigrant organizers to find another windmill to tilt at.” And then Downtown can go back to writing op-eds about “deep prosperity” and figuring out how to change things for the better without, you know, changing things.

But what Downtown hasn’t realized is that Metro hasn’t worked it all out. Metro, not exactly a bastian of MBAs and BSDs, has left out the whole other side of the equation what are our businesses — the brick and morters, from the wig stores and the restaurants to the Oracles and Accentures — signing onto when they install a Fusus box in their IT closet and send their data to Axon’s AWS cloud server?

What’s happening to it outside of what MNPD is doing with it?

From everything I’ve gathered in my reporting and searching through documents and archives, nobody knows. Except, we can assume, Axon.

The Friend of My Friend is My…

Metro, in fulfilling the task assigned to it from Downtown, went out and got a contract to “make Nashville safer.” And it seems like some of the Boomer leadership of Downtown, which is taking Metro’s word that they did the due diligence on this thing, is excited to get their Fusus boxes installed like they’re the first kid on the block to have Pong.

And why would Downtown be skeptical of Axon?

The folks who made those tasers that turned out to not always be “less than lethal”? The kind people that sued coroners for citing their products as causes of death??

The patriotic businessmen who are being sued for using Chinese electronic parts in their body cameras worn at election places???

Not my guys, Axon!!

Not the place where the CEO has pretended for decades that he was friends with two murdered boys from his high school to create a fictional, humble backstory for becoming a multimillionaire arms and surveillance dealer?????

And really, who is Downtown to look ascance at a company many of them share a lobbying firm with? “A friend of a friend is a friend!” - A wise business person never said.

It’s strange, but not unbelievable, that they haven’t run a background check on their new bosom buddy. Luckily I did for them. And Axon seems to be, in the words of a guy I never thought I’d quote, some “bad hombres.”

And their lack of any public T&Cs they’ll be asking every willing Metro Business to sign, is a major red flag to me.

I first raised my concerns about Axon on March 3rd, noting that Metro was moving toward passage of a contract, but no one seemed to have access to what the business’s side of the T&Cs were going to be.

Metro has not produced any indication about what they think the terms between Axon and residents would be.

Axon hasn’t answered questions on this topic either.

I believe they haven’t answered this because I am, to my knowledge, the first person who asked them this — on an email chain with every member of Metro Council visibly copied.

The response was: no response. Not even a confirmation of receipt.

Jar Jar Binks voice: How ruude!

No one from Metro, Axon, MNPD or elsewhere has indicated in any public forum I can find what conditions would be in the contracts between Fusus and resident “donor cameras” from busineses in Nashville.

There’s nothing online either. The “Fusus Terms and Conditions” are listed as “Third-Party-Terms” on Axon’s website. But when you click that link, it just takes you to a Fusus product marketing page with no terms and conditions to be found.

Serving One Master At a Time While Keeping the Backdoor Shut

My main concern about Axon having footage and AI processed analysis collected by publicly owned cameras around Nashville is who might have access to it besides MNPD.

The kinds of questions I asked Axon on Wednesday (to no response) were:

You’ve had over $26M of contracts with Federal agencies since 2020, including $14.6M with the Department of Homeland Security, and $7.7M with the Department of Justice. What confidence can you give Nashville that the provisions of our $750k contract and city ordinances will keep you from passing data from private citizens to the federal government extra-judiciously, similar to what competitors like Palantir do?

My point is basically that we know we’re on the weak side of this arrangement. We know the businesses sharing their data will be on an even weaker side. We know Axon is on the stronger side. But are there even stronger parties in this space, parties that could compel Axon to do things that they might not even want to do?

It’s the kind of thing we were asked all the time by HSBC or CitiBank, whose biggest risk was leaking out investment advice they didn’t actually care about. It’s not rude to ask these questions, it’s what you’re supposed to do in a country whose checks and balances are held together much more by tort law than government regulation.

Metro Government Leaders and Business Leaders wouldn’t be so flippant with their businesses data privacy as they are right now with the public’s. But the point I’m trying to drive home is that you are the public as well, and your data privacy, your company’s, is what’s at stake in things like this.

It would be really swell if our elected officials and the local business leaders pressuring them had one drop of that due diligence enthusiasm here. If not for the sake of innocent people who will suffer, than for your own bottom line and the security of your CEOs and intellectual property.

My first ever post on BlueSky was yesterday in response to a Metro Council Member defending his support of Fusus despite respecting women’s right to privacy regarding their reproductive health. I’ve avoided social media since the pandemic — but I couldn’t hold back explaining to the Council Member in terms relevant to his day job what’s going on here.

Although I used the acronym “EHC” instead of “EHR” for “Electronic Health Records”, my point is that if we just convert this into concepts we use every day at our day jobs, the red flags here start to really pop out.

I didn’t really get it until I started comparing this arrangement to the ones at my old employer. Quickly I realized “oh wow, we could never get away with this…”

Activists in Nashville and across the country are discussing the risk that increased surveillance causes for immigrants, trans folx, and women seeking basic reproductive care. This is, full disclosure, way more of a concern to me than business liability and corporate espionage. But this is written for folks who aren’t overly persuaded by concerns like that.

Things like Fusus, in my mind however, create great risks of liability for business leaders that don’t care about things like that, or at least don’t prioritize them above things like “making my city feel safe for new investors or high-skill employees that I want to move here.”

On those very terms, I’m trying to say to you, your investors and high-skill employees should NOT feel safer with privately controlled tech like this.

Without the right provisions in place, provisions that local, state, and even federal law probably do not have the teeth to implement (and now less than ever), the risk posed by mass surveillance controlled by for-profit corporations is just as high for corporate executives and intellectual property owners as for the trans teen who is worried about being arrested for wearing “drag”, or the Ukranian immigrant who lost their refugee status because Trump is mad as Zelinsky.

Without clear terms and conditions and evidence that we can have faith in Axon, how can we have confidence that the firm we’re feeding our cameras footage to?

If they were asked would they provide the images from our front lobbies and parking lots to the DOJ or FBI with or without a warrant, would they?

Would they provide AI-generated analysis about the activities of our product managers who are working on products that might seem like competition to folks in high levels of power who hate competition?

How many of you who read even a few of these articles about Axon’s past actions see a company with the ethics to turn down unlawful requests for data from a federal government that has enough contracts to make or break them in an instant?

And with perverse incentives and invisible strong sides at play like that:

How much privacy can a Nashville Product Manager working on a car line that’s attempting to outcompete Tesla, owned by DOGE’s leader Elon Musk, really expect when there’s integrated surveillance that can’t be controlled by local authorities?

What if Axon provides DHS or ICE recordings or livestream for our construction sites? Letting them watch for “Non-Americans” who are helping build a 28-story residential apartment complex or a 300,000 foot creative office space?

And what if they can not only find undocumented people on site, but by using the recordings of our workplaces filmed by other businesses’ Fusus cameras, and see that we maybe weren’t asking for status paperwork from our workers? Could we be charged under U.S.C. § 1324 with up to 10 years in prison for harboring illegal immigrants? — Or maybe just asked to make a sizable donation to a re-election fund to avoid jail time?

What if an American citizen is snatched up in an ICE raid near our business based on footage from our camera fed to DHS through Axon, and they are deported to another country, something that has happened many times. Are we, as the owners of the donor camera, liable in this massive civil rights violation?

To those of us whose eye’s on the world as it is right now, these are not dystopic visions of a future not likely to pass. Frankly, many of these things are just things that haven’t happened to someone you know — yet. And the other ones are commonplace to the extreme in countries that are further along the road we all know we are on.

If you're not worried about domestic state actors stealing your surveillance footage or data generated from it, what about other countries? Axon is facing a lawsuit over using Chinese-made tech in its body cameras worn at election sites. Security advocates are worried this could compromise election security, the hardware unknowingly (to Axon) perhaps being used to send data to the Chinese Communist Party. Axon refused to answer my question about the sourcing of their Fusus system’s hardware.

How many high-profile firms in Nashville or elsewhere love the idea that competitors or foreign governments might be able to observe where their employees go during and after work?

And I’ve gotta ask, as the child of two Air Force JAG lawyers that were introduced by future US Senator Lindsey Graham while they were all stationed together in Berlin in the ‘80s — how will all those national legislators and VIPs who come to Nashville to let off steam feel looking at all those cameras pointed at them recording video?

Video that’s not just going onto a private hard drive and erased within a week; video that’s not just going to local law enforcement if there happens to be an emergency in that vicinity; but video that might, just might, be scooped up by a $50B weapons and surveillance company, with some upcoming contract negotiations, that may want to leverage information about the goings and comings of public individuals who like to remain private.

Who, if not Nashville, is going to stand up for the privacy of ordinary, normal, all-American folks like Lindsey Graham, who just want to feel like they can move around our city without it becoming metadata leveraged against them the next time DHS needs to buy some tasers?